UMBRAIL – THE SWISS PATH

The Swiss border occupation 1914–1918

Follow in the footsteps of Swiss border guards. You will find traces of them on the way to Piz Umbrail and on to Punta di Rims. The route continues across Italian territory, taking a detour to one of the former Italian artillery positions before returning to the Umbrail Pass.

In the immediate vicinity of the Umbrail Pass (walking time up to 45 minutes), you will find information boards on the following topics:

-

- A comprehensive introduction to the situation during the First World War in the immediate border area

- The Swiss border defence system from the Dreisprachenspitze to Punta di Rims

- Tactical and combat considerations of the early 20th century

- Accommodation and fortifications

- Supply and logistics of the troops at ‘Umbrail Mitte’.

The route from Piz Umbrail (3,033 metres above sea level) to Punta di Rims and back to the pass provides:

-

- an overview of the history of events on the Ortler front;

- a general overview of the Swiss border occupation;

- the problem of border violations; and

- the significance of Italian artillery in the mountain warfare of 1915-1918.

Starting point and end point: Umbrail Pass summit

Walking time: 6 hours

Markings: white-green-red

Requirements: good physical condition, sure-footedness

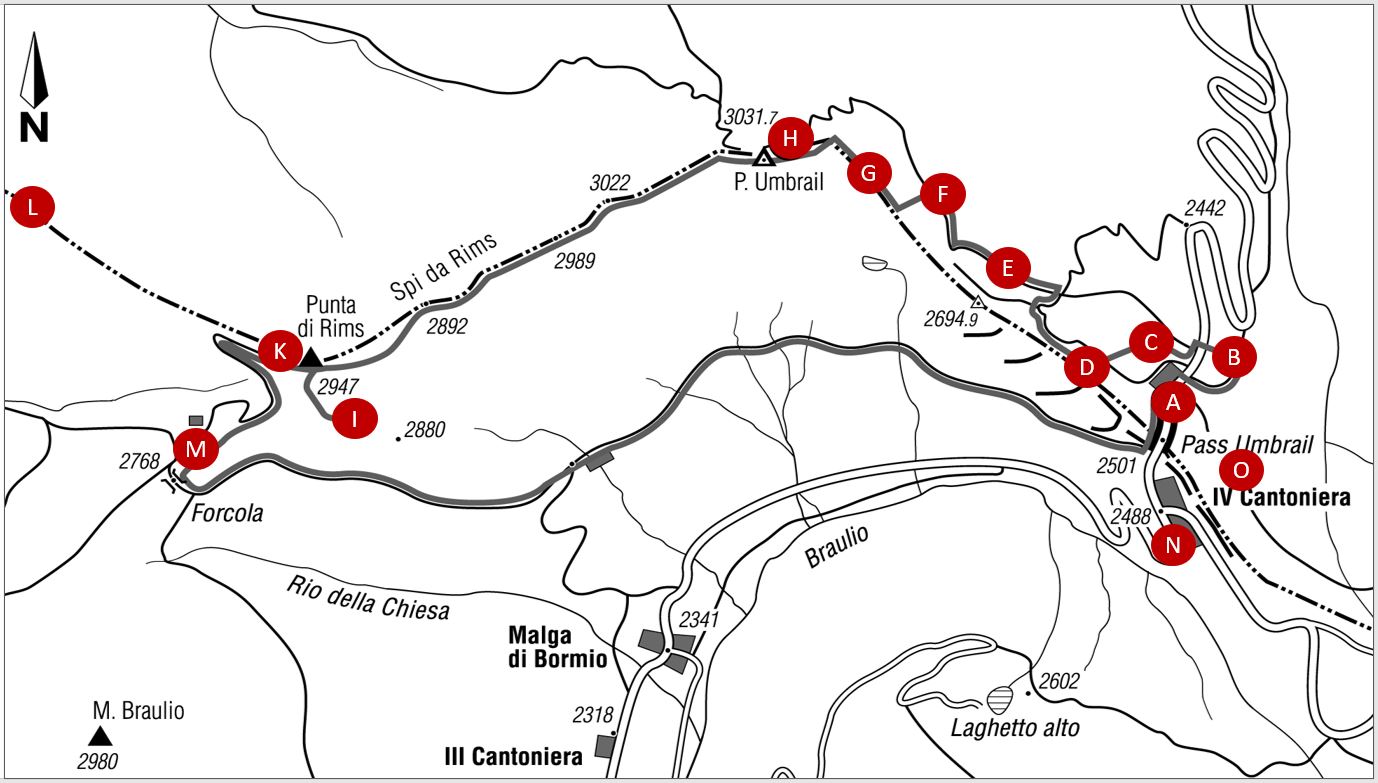

A: Starting point with group of figures 1914-2014 – B: Logistical facilities ‘Umbrail Mitte’ – C: Trenches – D: NCO post – E: Accommodation building – F: Bridlerhorst – G: Italian observation post on the Swiss border – H: Summit of Piz Umbrail, view of the Ortler front – I: Italian fortifications with cave positions – K: Officer post Punta di Rims – L: Border surveillance to Bochetta del Lago and Passo dei Pastori – M: Italian artillery position Bochetta di Forcola – N: Italian base at Quarta Cantoniera – O: NCO post ‘Splitterheim’.

A description of the route from a military history perspective

A detailed description of the route can be found in the hiking guide ‘Der militärhistorische Wanderweg Stelvio-Umbrail’ (The Stelvio-Umbrail Military History Trail) starting on page 36. The following information highlights places along the route and explains their historical significance.

The starting point …

Since summer 2014, the newly designed starting point of the Umbrail Trail has been located at 2,500 metres above sea level. Designed as both a monument and an information point, the structure was opened exactly 100 years to the day after the Swiss Army was mobilised on 2 August 1914. The installation was renovated in summer 2025.

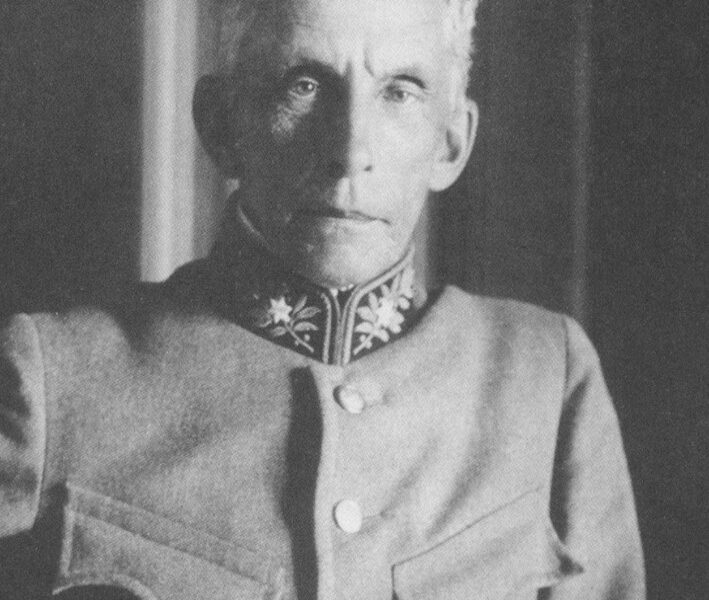

The square on the Umbrail Pass was designed by Duri Fasser, an artist from Val Müstair. Seven soldiers in their uniforms of the time stand guard together. They guard the knowledge of the events in the trilingual region. In the centre, the two most important Swiss protagonists of the First World War, General Ulrich Wille and his Chief of Staff Theophil Sprecher von Bernegg, face each other.

The 16 information boards in six languages (German, Romansh, Italian, English, French and Hungarian) convey the most important facts. As with all the information boards along the trails, the content and graphic design were created by David Accola, a former Swiss career officer and initiator of the ‘VEREINS STELVIO-UMBRAIL’ association.

To mark the centenary, the group of figures was installed on the Umbrail Pass with the support of many helpers.

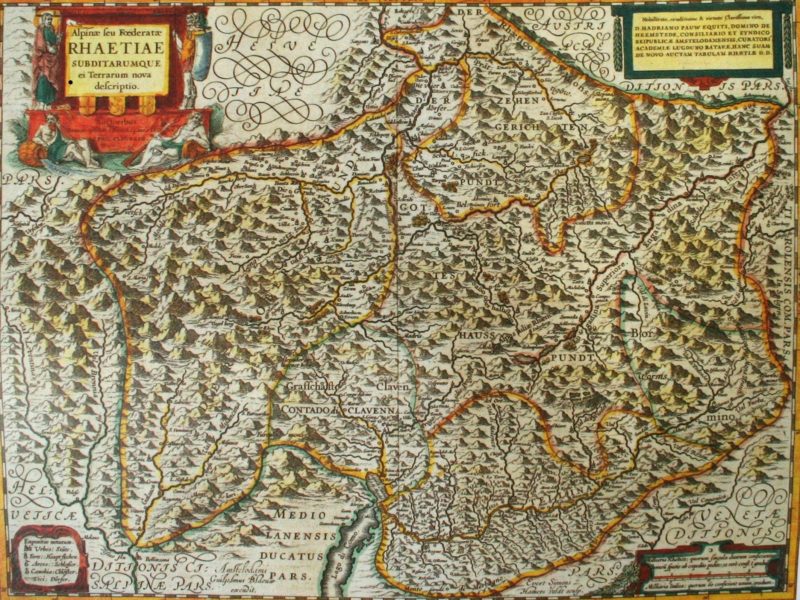

Pass da l’Umbrail – Giogo di Santa Maria – Wormserjoch

A pass with three names? Nothing unusual at the meeting point of three linguistic and cultural regions. The pass from Santa Maria in Val Müstair to Bormio (German: Worms) in Valtellina was of great importance for medieval trade, as the mountain pass at 2,500 metres above sea level was the shortest route between Venice and Milan in the area north of the Alps. Salt from the mines of Tyrol was transported south for food preservation, while wine barrels made their way north via the mule track. Even back then, the transport of goods was strictly organised and regulated.

The supply chain ran from transhipment point to transhipment point, where the goods were temporarily stored or transhipped. For example, muleteers from Tyrol had the exclusive right to transport goods from Innsbruck or Landeck via the Reschen Pass to Val Müstair. There, local muleteers took over the goods and carried them over the pass to Bormio, where they were handed over to the next ‘transport company’. Goods were transshipped in the Münstertal valley in Sta. Maria, where they were temporarily stored in the Chasa Plaz – in the rooms of today’s ‘MUSEUMS 14/18’.

From 1512 to 1797, the Valtellina belonged to the subjects of the Free State of the Three Leagues. Chiavenna (Cläven) – Piuro (Plurs) – Sondrio – Tirano and Bormio (Worms) belonged at that time to what is now the canton of Graubünden, which only became a full member of the Swiss Confederation in 1803 as a former ‘associated territory’. For 285 years, the Umbrail Pass was therefore an internal cantonal link.

Unrest and uprisings in northern Italy, which was then part of Austria, at the beginning of the 19th century – primarily in Milan – prompted the House of Habsburg to consider planning a military road to the region. The aim was to be able to move troops quickly to Milan if necessary. Switzerland rejected Austria’s proposal to expand the mule track over the pass at its own expense. Although the project was lucrative, the neutrality of the Swiss Confederation declared at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 gave rise to reservations. A passable road: yes, please; a military road for foreign armed forces: out of the question! The result was the construction of the road over the Stelvio Pass. Further details can be found on the page ‘Trais Linguas’.

Construction of the current road began in 1898 and just three years later, on 19 July 1901, the connection was officially opened. The road was initially only open to horse-drawn vehicles, but soon after it was also opened to the sparse motorised traffic that was beginning to emerge.

The construction costs for the 13,390-metre-long road amounted to 271,143 Swiss francs and, as is usual with construction projects, were higher than originally estimated. The price at that time corresponds to a value of around 3.4 million Swiss francs today.

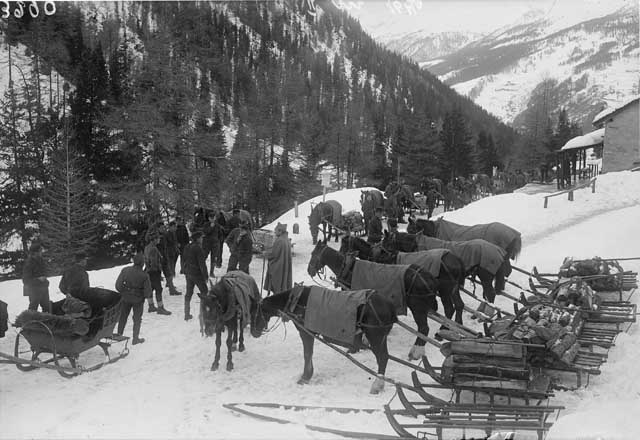

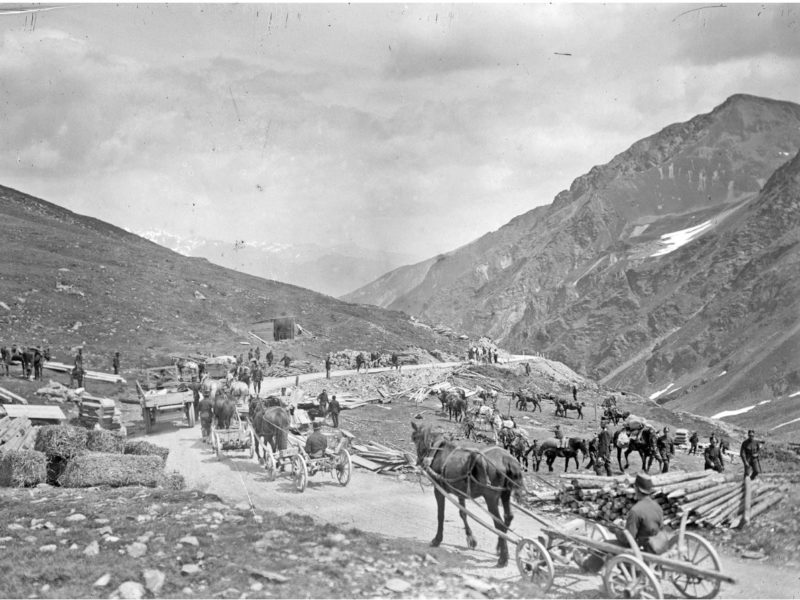

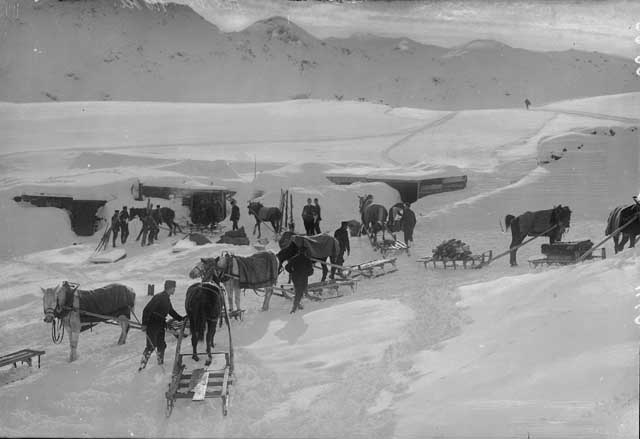

During the First World War, supplies were delivered to the Umbrail soldiers along this route. The road was closed to cross-border traffic and, during the snowy months, the now militarised packers continued to transport all necessary goods over the pass.

Goods necessary for war

According to reliable sources, it can be assumed that up to 600 soldiers had to be supplied at the Umbrail Pass at times. This task required a great deal of logistical effort in the high-altitude positions and especially in the valley. The supply of food was the least of the challenges. The supply of wood was essential for building shelters and heating them. Attentive visitors to the pass region will notice the scarcity of water sources. Most of these dried up in the winter months, so that drinking water could only be obtained by melting snow. This meant that additional fuel was required.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the tree line in this region was at an altitude of around 2,000 metres above sea level. According to calculations, heating the shelters alone during the four years of war required wood from an area of forest roughly the size of 90 football pitches. The trees were felled near the pass road, prepared and stored. The transhipment point was located between Plattatschas (now the ‘Alpenrose’ inn) and Punt Teal.

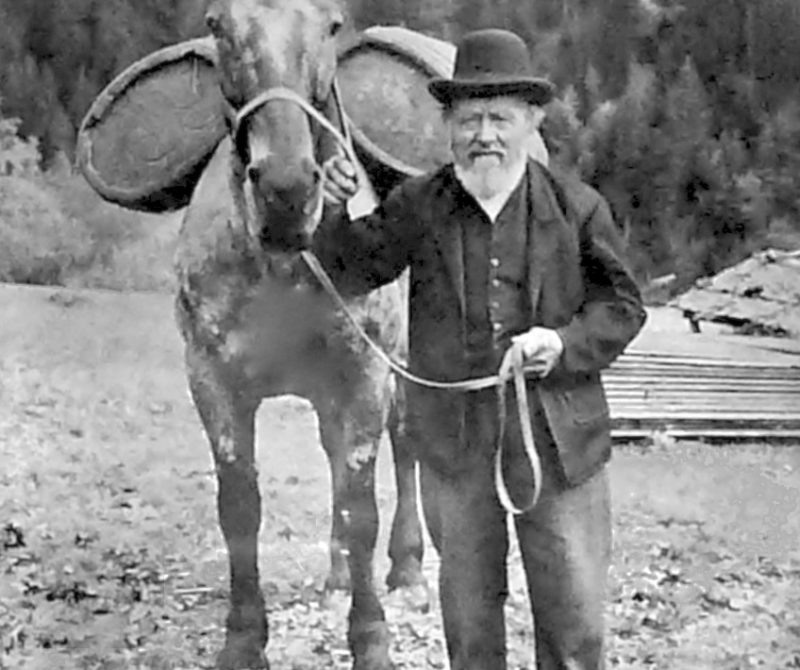

The goods were transported to the top of the pass with the help of horses. In summer on carts and in winter on sledges, convoys of pack animals carried the necessary goods to the top of the pass, just as they had done in the Middle Ages. Some of the horses were stabled in the valley, but most were kept on the Muraunza alp. The mountain stream (Muranzina) flowing through the alp provided a regular source of water for the horses. The foundation walls of the stables are still clearly visible today.

The inn on the Muraunza Alp (pictured here around 1920) was the only permanent accommodation along the supply routes, apart from the hotel on the Dreisprachenspitze. Source: Federal Archives, inventory E 27, archive: MUSEUM 14/18

Umbrail Pass: the logistical hub

A few metres before the top of the pass, coming from Val Müstair on the left-hand side, we can see foundation walls and fortified tracks. These are located around 100 metres to the left of the road, just before the pass, and cannot be missed.

This is a six-part building complex referred to in the records as ‘Umbrail Centre’.

This is where the central kitchen, a sick bay, equipment stores, a shelter for a few horses and the necessary accommodation for the operating personnel were located. The sparse water source, the proximity to the pass road and the secure location on the military rear slope were certainly reasons for establishing the logistical centre of the Umbrail soldiers here.

Centre of Umbrail on a drone photograph (2013) taken by the Archaeological Service of the Canton of Graubünden. From left to right: horse stable, accommodation building ‘Stafelegg’, infirmary, kitchen building. The water source that was decisive for the choice of location can be seen on the far right of the picture.

Impressive and impossible to miss – the trench system

The trench system between the pass summit and the foot of Piz Umbrail stretches for a good kilometre. The first 400 metres of this ‘snake line’ are clearly visible from the pass summit. The trench and firing line runs a few metres inside the actual border and is ‘interrupted’ by numerous sapings. Sapings are the conspicuous indentations in the line that provided additional protection for the troops.

The trench system at the Umbrail Pass in a drone photograph (2013) taken by the Archaeological Service of the Canton of Graubünden. In the right-hand third of the image, the fortifications can be seen directly on the border, while on the left, on the rear slope, are the foundation walls of the huts and the access routes to the fortifications.

Sappen and their protective function

The construction of a straight combat trench was naturally much less labour-intensive than that of the sapped variant. However, its protective function was severely limited. If the enemy managed to penetrate a straight trench, all defenders were in the same line of fire. The firepower of the intruder was correspondingly high and the defending soldiers had no opportunity to seek cover. Even with indirect fire from artillery or hand grenades, the shrapnel effect could not be stopped.

These risks could be minimised with a snake-like system of trenches interrupted by saps. There were perhaps three or four soldiers in the projectile’s field of effect, rather than 30, assuming that the position was manned by a platoon.

The sap variant was mainly used where defensive trenches were part of an overall defence system. Their construction was planned over the long term and carried out in an optimal manner for combat, i.e. along a ridge line. Access was via the corresponding rear slope, which meant that no additional trenches had to be built. Trenches that were offensive in nature and only intended to provide temporary protection, on the other hand, were built in straight lines and were hardly fortified. They served to protect small detachments at specific points and were only exceptionally part of an overall concept.

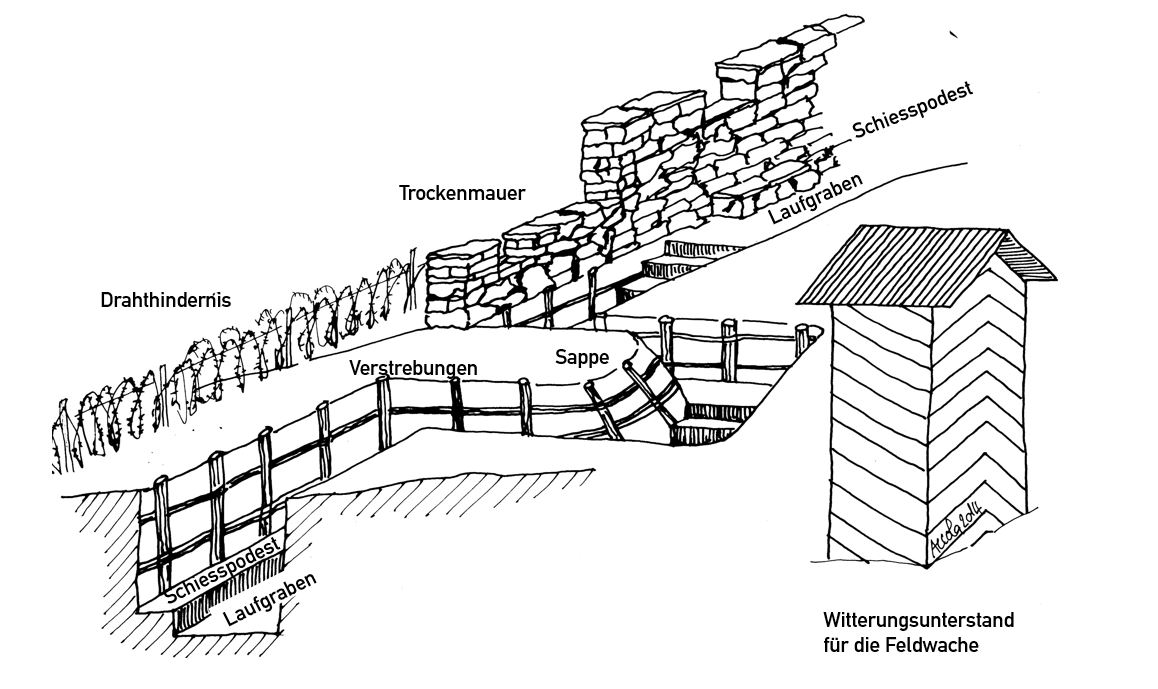

Symbolic representation of the different construction methods used in the trench system. Sketch: Accola

The Umbrail position as part of the defence strategy

To understand the importance of the positions on the Umbrail Pass, it is necessary to understand the large-scale strategy for the territorial defence of the canton of Graubünden during the First World War. This was based on the assumption of a threat and the conviction that the terrain was the defender’s strongest ally.

The threat assumption

Theophil Sprecher von Bernegg, then Chief of the General Staff Department, assessed the European situation for Switzerland as early as 1906 as follows:

- A war between France (Entente) and the German Empire (Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Italy) is likely;

- a war between Austria-Hungary and Italy was conceivable if Italy switched sides to the Entente and was thus able to assert its territorial interests;

- Italy’s territorial interests basically encompass all Italian- and Ladin-speaking areas, based on the irredentist idea that a population speaking the same language should belong to the same state. There were also corresponding areas of interest in Switzerland, primarily in Ticino, but of course also in the southern valleys of Graubünden and the Engadin.

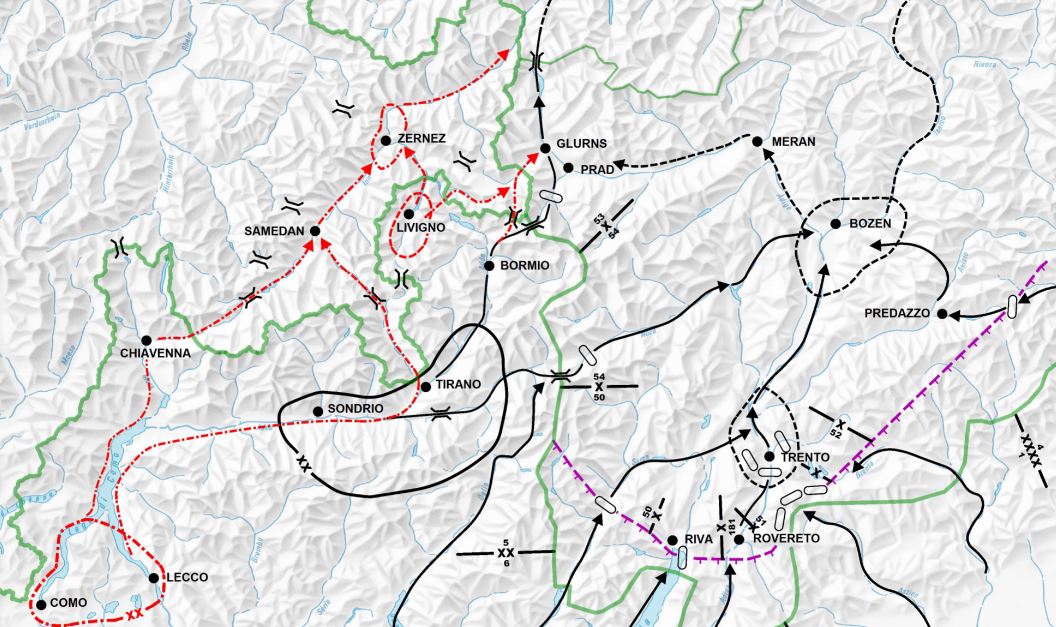

The Italian forces had the following areas at their disposal as suitable staging grounds for an invasion of the canton of Graubünden (we are deliberately excluding Ticino here):

- The Chiavenna area, with the possibility of advancing directly into the Bergell valley or reaching central Graubünden via the Splügen Pass;

- The lower Valtellina (Sondrio-Tirano) – with the possibility of advancing into the Upper Engadine via Poschiavo and the Bernina Pass;

- The upper Valtellina (Bormio-Livigno) – with the possibility of reaching the Münstertal and the northern part of South Tyrol (then Austria-Hungary) via the Umbrail Pass or advancing directly to Zernez.

If the Engadin were in the hands of the Italian invaders, their intention would certainly be to occupy the Alpine passes within the canton (Julier, Albula and Flüela) and secure the necessary flank protection there.

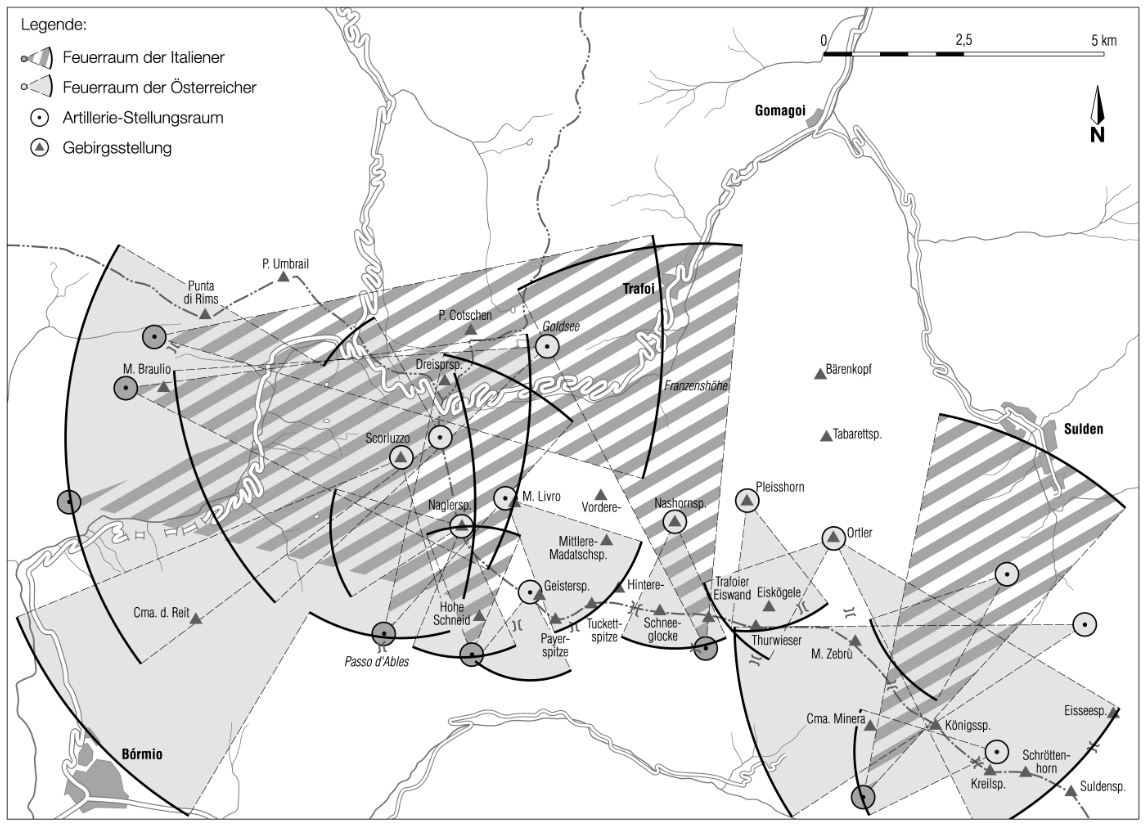

Italian attack options for advancing into Trentino and South Tyrol. The options that could be used to bypass Austrian defensive positions by utilising Swiss territory are shown in red. Map: Accola, published in the article Fuhrer in the commemorative publication Rauchensteiner (Politics and the Military in the 19th and 20th Centuries), 2017.

The operational concept for the defence of the canton of Graubünden

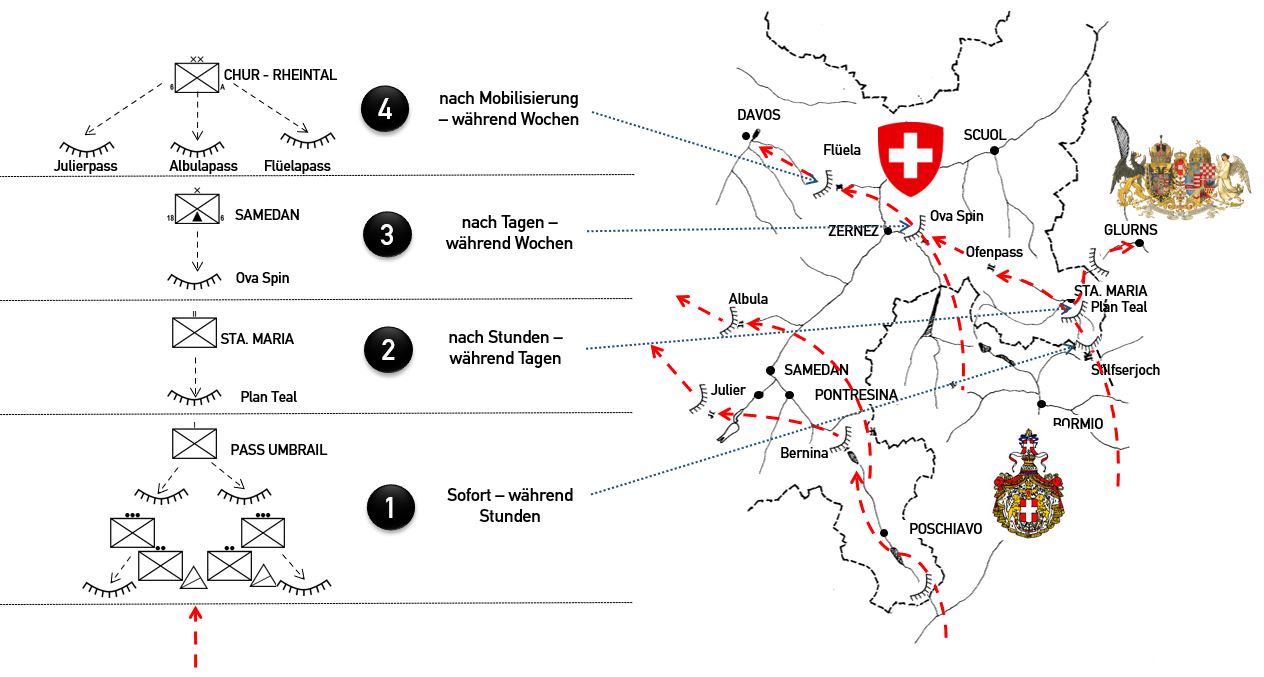

Sprecher’s plan was designed accordingly. Italian troops were to be intercepted near the border and their advance delayed long enough to allow Swiss troops to establish a first line of defence. This idea applied to battalions as well as brigades and even divisions. Applying this plan to the Lower Engadine and Val Müstair region results in the following spatial arrangement.

On the Umbrail Pass, the attacker was to be held up for hours by a so-called outpost company in order to give the reserves in Val Müstair (a company of the outpost battalion) enough time to take up a second defensive position at the tree line near Plan Teal.

Their task was to hold back the enemy for days, thereby gaining the time necessary for troops from the brigade in Samedan to take up defensive positions at Ova Spin (on the Ofen Pass road).

Their task, in turn, was to delay the enemy for weeks, allowing division troops to set up and occupy defensive positions in the inner Grisons passes.

The rugged terrain made this plan credible, and the amount of material and soldiers required was enormous, to say the least, for an attacker.

Operational plan to delay an Italian advance into Graubünden. Illustration: Accola, MUSEUM 14/18, special exhibition 2014.

The first line of defence – the ‘UMBRAIL device’

It is not customary for operational commanders to specify at the tactical level how their intentions are to be implemented. However, as we all know, exceptions prove the rule – and Umbrail is a case in point. The decision to deploy the company was made at the highest level. The Chief of the General Staff personally ordered how his defence concept was to be implemented at this level by individual officers and soldiers. Why Sprecher allowed himself to be drawn into this ‘faux pas’ is not documented – but there are plausible reasons for his attempted justification.

- Von Sprecher knew the region like the back of his hand, having grown up in Graubünden. Although he had absolute trust in his subordinate, Brigade Commander Otto Bridler, the corps commanders he had ordered into action knew the area at best from hearsay.

- Von Sprecher knew the field service regulations, having played a key role in drafting them, and knew which level of authority was responsible for what. Based on this, he most likely wanted to prevent the situation from escalating due to the ‘carelessness of a trigger-happy officer’. A state of war between Italy and Switzerland – caused on an inhospitable mountain pass of little significance to the Swiss Confederation – had to be prevented.

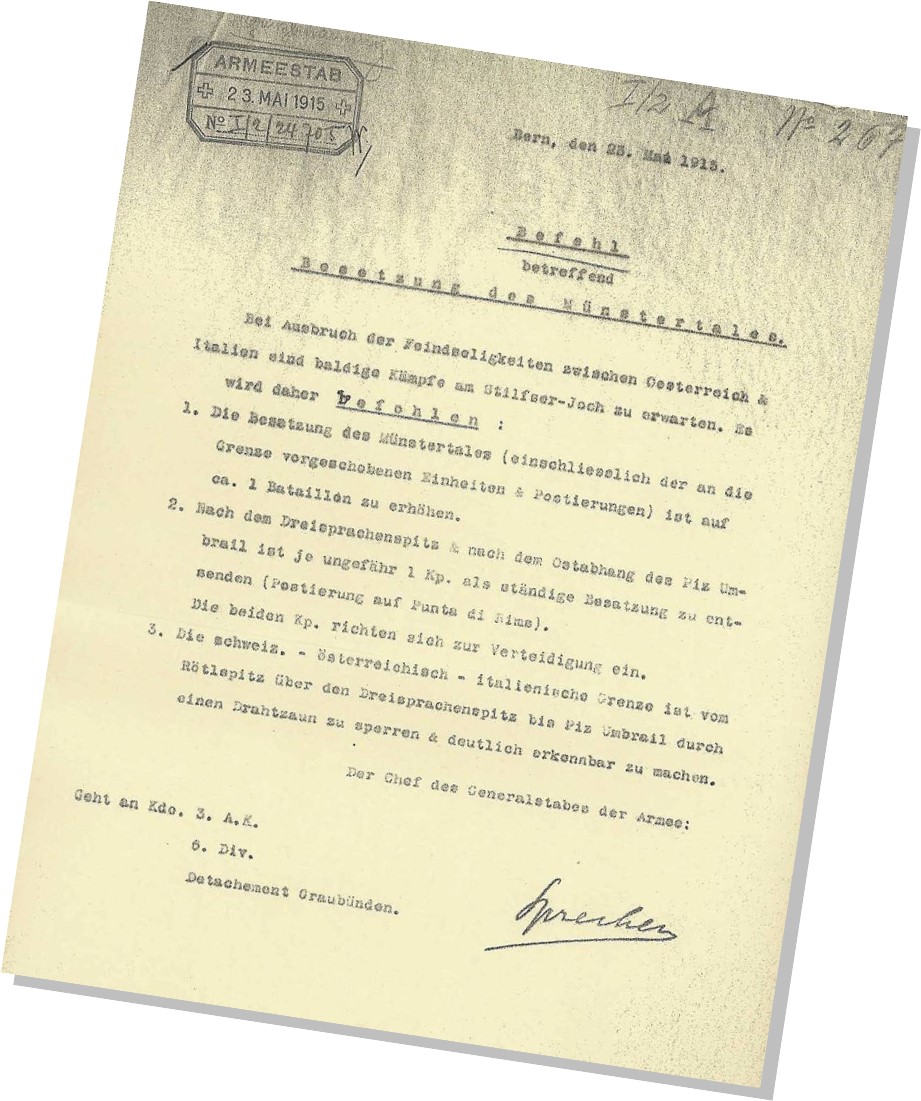

Von Sprechers order of 23 May 1915, on the day Italy declared war on the Austrian Emperor, was as follows:

„With the outbreak of hostilities between Austria and Italy, fighting is expected soon at the Stelvio Pass. The following orders are therefore issued:

- The occupation of the Münstertal valley (including the units and positions advanced to the border) is to be increased to approximately 1 battalion.

- Approximately one company is to be sent as a permanent garrison to the Dreisprachenspitz and to the eastern slope of the Piz Umbrail. (Position on the Punta di Rims). The two companies are to prepare for defence.

- The Swiss-Austrian-Italian border is to be blocked by a wire fence from the Rötelspitz via the Dreisprachenspitz to the Piz Umbrail and made clearly visible.“

Theophil von Sprecher’s ‘Order concerning the occupation of the Münstertal’ dated 23 May 1915. Source: Federal Archives, inventory E 27, archive: MUSEUM 14/18

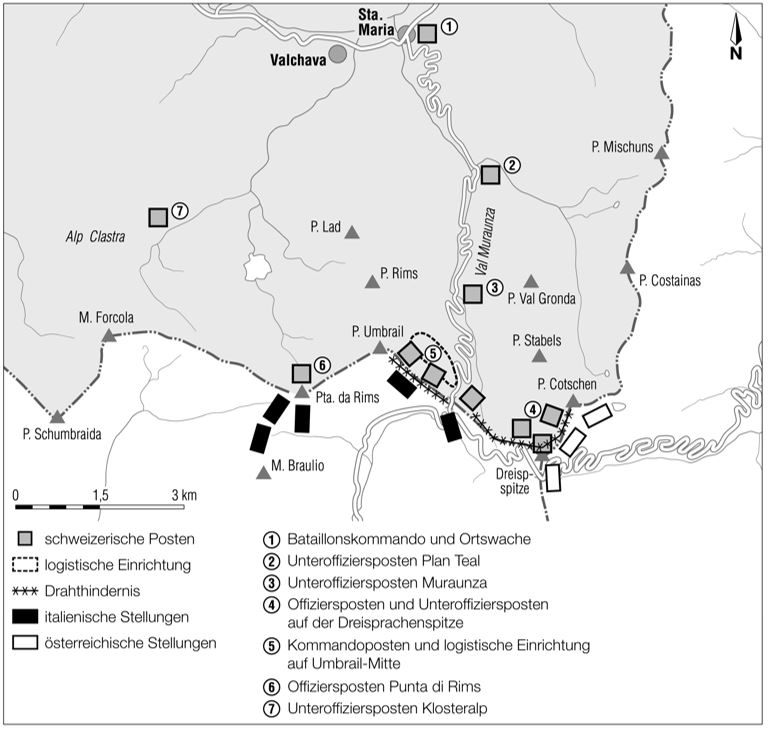

Soldiers in Val Müstair

The battalion set up its headquarters in Sta. Maria and occupied several houses in the village, including the Chasa Parli, the Chasa Plaz and the ‘Crusch Alva’.

Two units of the battalion remained in the valley and manned the security posts on the Alp Clastra (two non-commissioned officers with seven fusiliers) and at the border crossing in Müstair (one officer, three non-commissioned officers and 18 fusiliers). These two units also manned the non-commissioned officer posts at the Plan Teal house (Alpenrose restaurant on Umbrailstrasse) and at the Muraunza inn. The latter two posts were responsible for organising and carrying out necessary goods transports over the pass and were reinforced accordingly with road workers, packers, telephone operators and, of course, numerous pack animals, carts and sledges. Roughly speaking, there were 10-12 soldiers at each of these two locations.

Another task in the valley was to protect the military accommodation and facilities and to enforce order within the framework of the service. This task was carried out by the local guard.

The remaining soldiers stationed in the valley were often engaged in monotonous training, were used for wood processing or supported the local population with various tasks, especially during the harvest season. It is often forgotten that the men from Val Müstair were conscripted into military service, which also applied to the horses that otherwise supported the farmers‘ work.

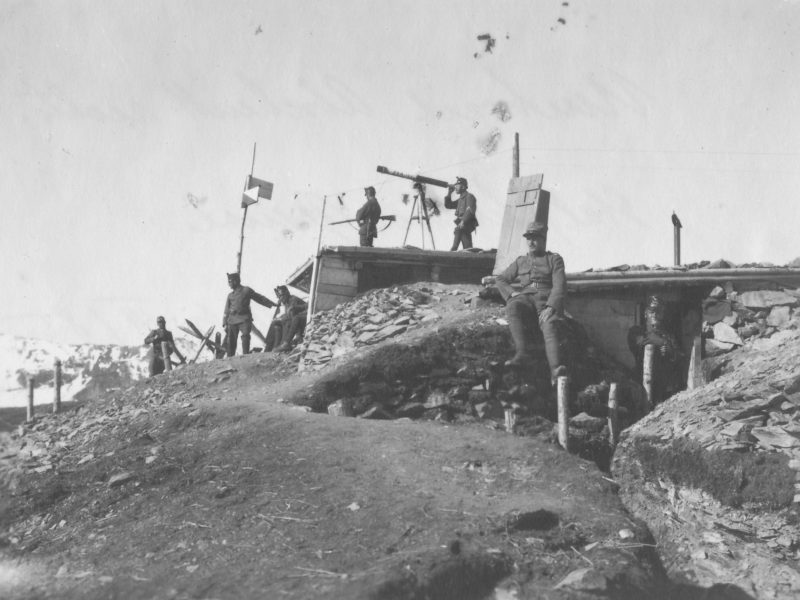

Soldiers occupy the border

Two units were stationed on the pass itself to secure the border. The centre of the border defence system was the pass itself.

An officer’s post was set up on the Punta di Rims, whose task was to monitor Italian activities along the northern border and, in particular, to report on their actions in the nearby artillery position ‘Bochetta di Forcola’.

Another officer post was established on the Dreisprachenspitze. Further information on this ‘hotspot of the border occupation’ can be found in the section on the ‘Trais Linguas’ section of the route.

The border between these two ‘cornerstones’ was protected by the so-called non-commissioned officer posts, which were set up along the trench system. These posts were each manned by a group (one non-commissioned officer and eight soldiers) and observed activities in the immediate vicinity of the border. This often led to personal contact between the Alpini and the fusiliers, and souvenirs or even food were often exchanged. There was no sign of hostility. The situation only became challenging when Italians attempted to cross the border – not with hostile intentions, but rather with the desire to quit military service and be interned in Switzerland. The number of deserters was considerable and the risk they took was very high. If they managed to escape across the border, they were assured of protection, but if they failed, the deserters were often shot by their comrades under martial law.

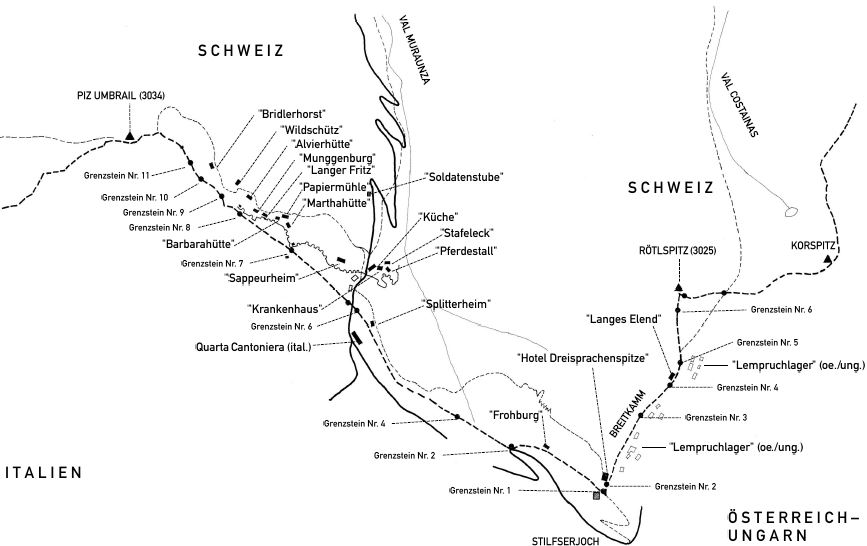

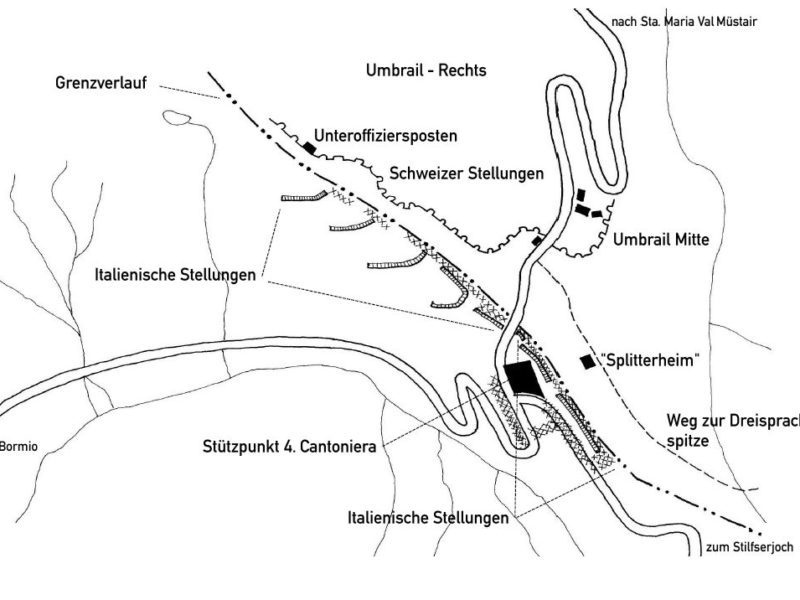

The border protection system between Punta di Rims and Dreisprachenspitze. Illustration from: Accola/Fuhrer, Stilfserjoch-Umbrail 1914-1918, Documentation, Military History You Can Touch, Au, 2000.

Officer and non-commissioned officer posts

The outpost companies tasked with protecting the border were organised into various posts with corresponding responsibilities. Officer posts were stationed at Punta di Rims and Dreisprachenspitze. These bases were largely self-sufficient, and their commanders – usually experienced first lieutenants – led around 50 men in these elevated positions. The powers of the commanding officers were laid down in the 1914 Field Service Regulations, in particular their authority to open fire in the event of an enemy attack.

Non-commissioned officer posts were usually manned by eight men under the command of a sergeant or corporal. Their task was to observe enemy activities along the border and, if possible, alert rear reinforcements. Engaging in return fire was not within their authority and required the approval of the unit commander. The latter, in turn, had to obtain the corresponding consent from the battalion.

Roofs over the heads of the Umbrail soldiers

The permanent presence of troops in the high ground from May 1915 onwards required solid, winter-proof accommodation. Protection from the elements was essential, and warmth was vital for survival. Snow depths of up to four metres and temperatures as low as 40 degrees below zero were not uncommon during the long winters. Heavy rainfall, lightning and thunder also made dry, wind-protected shelters necessary in summer.

In August 1914, the Umbrail soldiers sought shelter in trenches covered with tent tarpaulins. However, a shelter plan had to be implemented quickly to enable them to stay during the winter months. There was very little accommodation available near the border: there was an Austrian-owned hotel on the Dreisprachspitze, and the 4th Cantoniera (road maintenance depot at the customs crossing) was located in Italy and used by the financial police. With the exception of a shepherd’s hut, there was nothing at all on the Umbrail Pass, and the Muraunza inn was small and had long since seen better days after the decline in mule traffic.

During the winter of 1914/1915, Bridler reduced the presence at the border to such an extent that no troops had to be accommodated at Umbrail. The pass roads were all closed (winter closure) and there were no disputes (yet) between Italy and Austria-Hungary. With Italy’s declaration of war on the Austrian Emperor on 23 May 1915, this changed abruptly and the new situation required the measures laid down in the order of the Chief of the General Staff (see above).

Lively construction work on positions and accommodation now began, which was to continue until the end of the war.

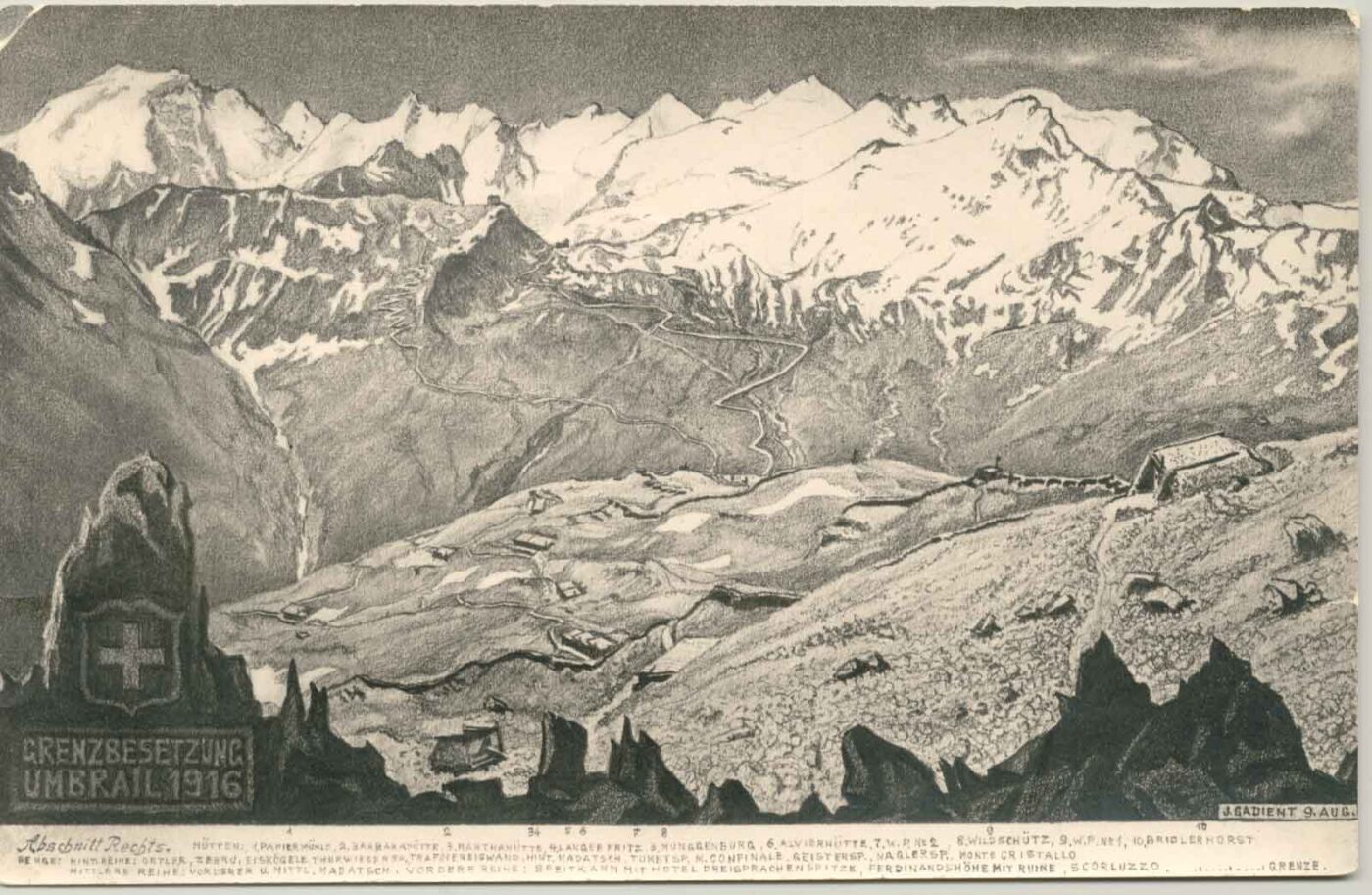

An overview of the accommodation huts on the rear slope. Field postcard by J. Gadient, dated 9 August 1916. Image: Gustin Collection, MUSEUM 14/18 Archive.

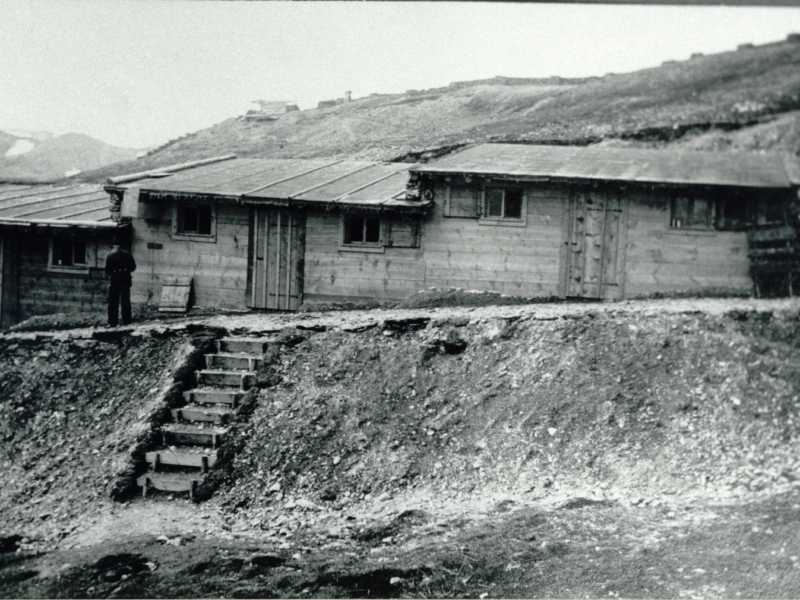

Members of Landwehr Battalion 164 erect the ‘Stafelegg’ barracks at Umbrail-Mitte. Crew lists indicate not only the origin but also the professions of the Umbrail soldiers. Most of them had pursued a trade in civilian life, so that their skills could also be used for military purposes. The military construction specialists, the ‘sappers’, were mainly involved in the construction and maintenance of roads and bridges. Image: Gustin Collection, MUSEUM 14/18 Archive.

The ‘Lange Fritz’ (Tall Fritz) – named after battalion commander Major Fritz Baumann. He commanded Battalion 76 until the end of 1914, so he did not lead his troops on the Umbrail Pass. Why he was given the honour of having the battalion named after him is unknown. Image: Gustin Collection, MUSEUM 14/18 Archive.

Location and names of all accommodation huts and structures on the Umbrail Pass and the Dreisprachenspitze. Illustration: Accola

the italian observation post on Piz Umbrail

The hiking route of military-historical interest leaves the official hiking trail at the ‘Bridlerhorst’ and climbs to the left over striking boulder fields to the south-east ridge of Piz Umbrail. This route is also known as the ‘winter route’ by ski tourers, as crossing the eastern flank of Piz Umbrail (summer route) is often too risky in winter.

This trail to the summit requires good surefootedness in summer. It is reserved for experienced mountaineers and the route is secured in places with chains and ropes.

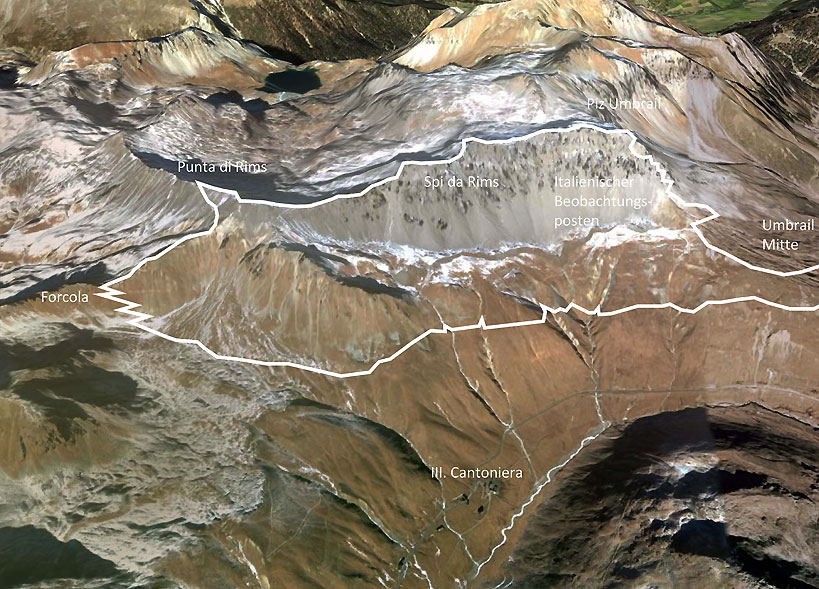

At an altitude of 2840 metres above sea level, we come across an Italian observation post, which was built in a dominant rocky outcrop. This rocky outcrop lies exactly on the national border and it was long disputed whether this lookout post was on Italian or Swiss territory. However, the latest maps show the point on Italian territory, albeit only by a few metres.

The occupation of this observation post is very poorly documented. There are no documents in Italian archives that provide information on this. However, we know from accounts of the Swiss intelligence service that the post was operated from the Italian flank position on Punta di Rims. Access was along a track along the foot of the south face of Piz Umbrail, which can no longer be found today. The fact that no other infrastructure can be found in the immediate vicinity of the post suggests that this location was only used sporadically as an observation post.

However, the telephone line leading there from the III Cantoniera suggests that this observation post was of great importance as part of the defence against an Austrian attack to guide the artillery fire.

The view from the rock window of the observation post. With good visibility, the Italians were able to detect the activities of the Swiss soldiers on the rear slope and at the same time recognise movements in front of the Stilfserjoch.

The Ortler front

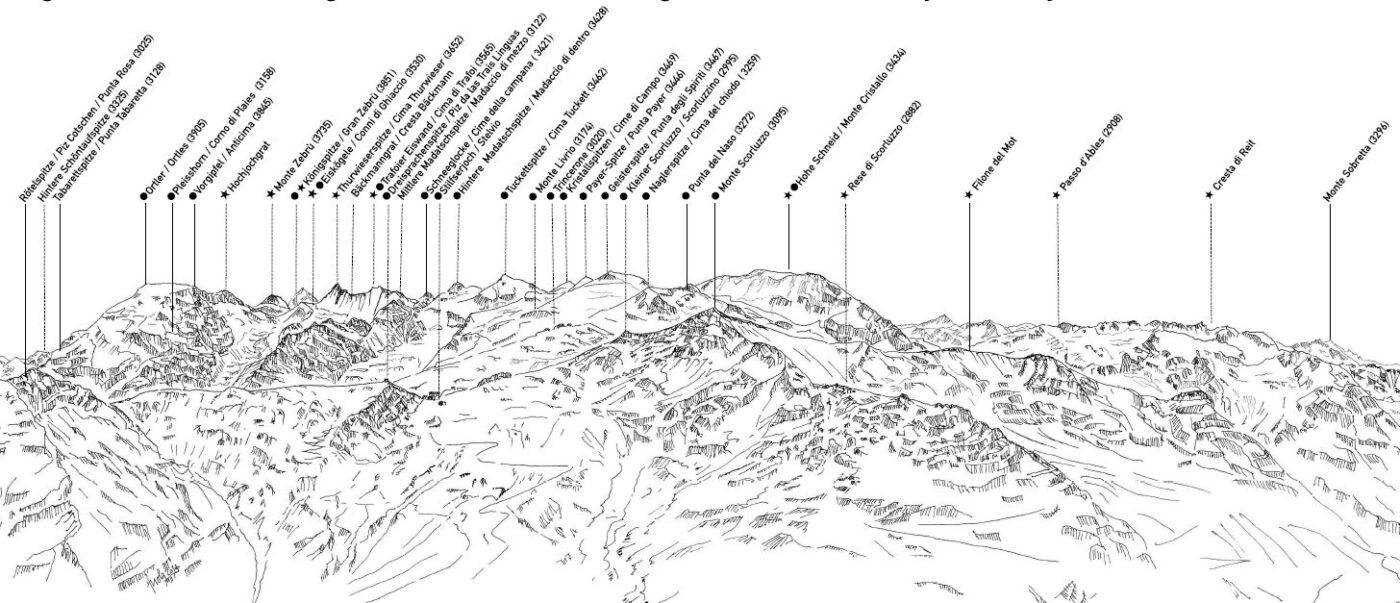

On the summit of Piz Umbrail (3034 metres above sea level), the impressive panorama to the south provides a view of the course of the former front along the horizon.

The positions recognisable from the summit of Piz Umbrail along the Ortler front: the sketch below shows the Italian positions with stars and the Austro-Hungarian positions with black dots.

Sketched summit panorama from Piz Umbrail to the south; Illustration: Accola

From Piz Umbrail to Punta di Rims

Many hikers leave the summit in a north-easterly direction to descend back into the valley via the Lai da Rims. Although this jewel of the Val Müstair should definitely be visited at least once, the military-historical route follows the border ridge from the summit in a south-easterly direction.

the italian flank position

At the lowest point of the ridge, shortly before it rises again to Punta di Rims, a track leaves the ridge in a southerly direction. This track runs exactly along a former wire obstacle that the Italians had erected to protect the flanks of their artillery position behind it. The foundations of former accommodation buildings can be seen on the rear slope and the observation hatches of the observation posts can be recognised in the rock tower in front of us.

The officer’s post on the Punta di Rims

The view from the summit of the 2945 metre-high scree pyramid of Punta di Rims to the south-east clarifies the question of why Switzerland operated a remote officer’s post here. The Italian artillery emplacement ‘Bochetta di Forcola’ lies at its foot. Access to this post was via the previously travelled path. Every piece of firewood and timber had to be transported here on foot. Carrying animals could only be used as far as the foot of the Piz Umbrail wall (at the height of the Bridler-Horst). Water was in short supply, especially during the summer, so rainfall was very welcome. The way in which the nearby spring on Italian soil was used is not documented. However, it can be assumed that the lively exchange of goods between the Italians and Swiss on the summit occasionally included barrels of drinking water.

Remaining masonry of the Italian shelters on Punta di Rims. Photo taken from boundary stone no. 12, showing the further course of the border along the ridge and, at its lowest point, the ‘Bochetta del Lago’, which was monitored by patrols from the summit crew.

The ‘Bochetta di Forcola’ artillery emplacement

The cavernous guns along the ridge from Punta di Rims to the crossing some 300 metres below belonged to the Forcola gun group. Further guns were located on Monte Braulio and Corne di Radisca. Guns and ammunition were transported from the Valle di Fraéle to these high-altitude positions via fixed roads, which are still in good condition today.

Areas of effect of the artillery used. The description is not exhaustive. Guns from the Forcola area were able to reach Trafoi, but only by accepting a Swiss border violation. Illustration from: Accola/Fuhrer, Stilfserjoch-Umbrail 1914-1918, Dokumentation, Militärgeschichte zum Anfassen, Au, 2000.

From the ‘Bochetta di Forcola’ to the IV Cantoniera

The descent is a short, steep descent towards Valle del Braulio. Following the previously described flank to the south, the path soon passes the Rio del Gesso (gypsum stream) and the Baitello del Cögno (cattle shed). Remaining at the same altitude, we reach the Umbrail road at the Italian border crossing after a good 1.5 kilometres.

The Italian base at the IV Cantoniera and the ‘splinter home’

Road maintenance centres – Italian Cantoniere (plural) – were set up to maintain the Stelvio Pass road during its construction. There were four of them along the stretch from Bormio to the top of the pass, which were labelled with corresponding numbers. This fourth, the Quarta Cantoniera, was located at the border crossing to Switzerland. In peaceful times, all customs traffic was handled in this cantoniera – there were no identity checks anywhere in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century – and cross-border goods traffic brought in money.

When war broke out, this Cantoniera was developed into a military base and protected by wire obstacles, trenches and weapon positions. The course of these fortifications is still clearly recognisable today. The Austrian shelling of this base is also evidenced by the bullet craters that can be found.

However, the artillery bombardment of the building located directly on the Swiss border was associated with the risk of violating neutrality, so that the number of such attacks remained manageable. But they certainly made an impression on the Swiss soldiers. The NCO post in the immediate vicinity was also known as the ‘Splitterheim’ in soldier’s jargon – an unmistakable sign that the air here was more ‘leaden’ than elsewhere on the Umbrail.

Would you like to walk the Umbrail trail with an expert guide?

You are in good hands on this page.