TRAIS LINGUAS – THREE LANGUAGES – TRE LINGUE

AUSTRIA/HUNGARY’S BATTLE FOR THE STELVIO PASS

Until 1918, the border between Italy and the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy ran across the Stelvio Pass. A border that was bitterly fought over during the years 1915-1918. Follow the traces of this turbulent time that can still be found today. The ‘Trais Linguas’ (three languages) trail will give you an understanding of the Austro-Hungarian perspective.

The following topics are highlighted in the immediate vicinity of the three-language peak:

-

- the defence system of Austria-Hungary;

- the old Austrian troops in the battle area of the Stelvio Pass;

- the war on peaks and ridges along the Ortler front;

- the accommodation and supply situation;

- border and neutrality violations – the role of Switzerland;

- the importance of Austrian artillery in the mountain war 15/18.

Starting and finishing point: Stelvio Pass – pass summit (access from Pass Umbrail via Swiss territory possible)

Walking time: 2 ½ hours (from the Stelvio Pass)

Marking: white-green-red

Requirements: easy walk

ROUTE GUIDANCE ‘TRAIS LINGUAS’

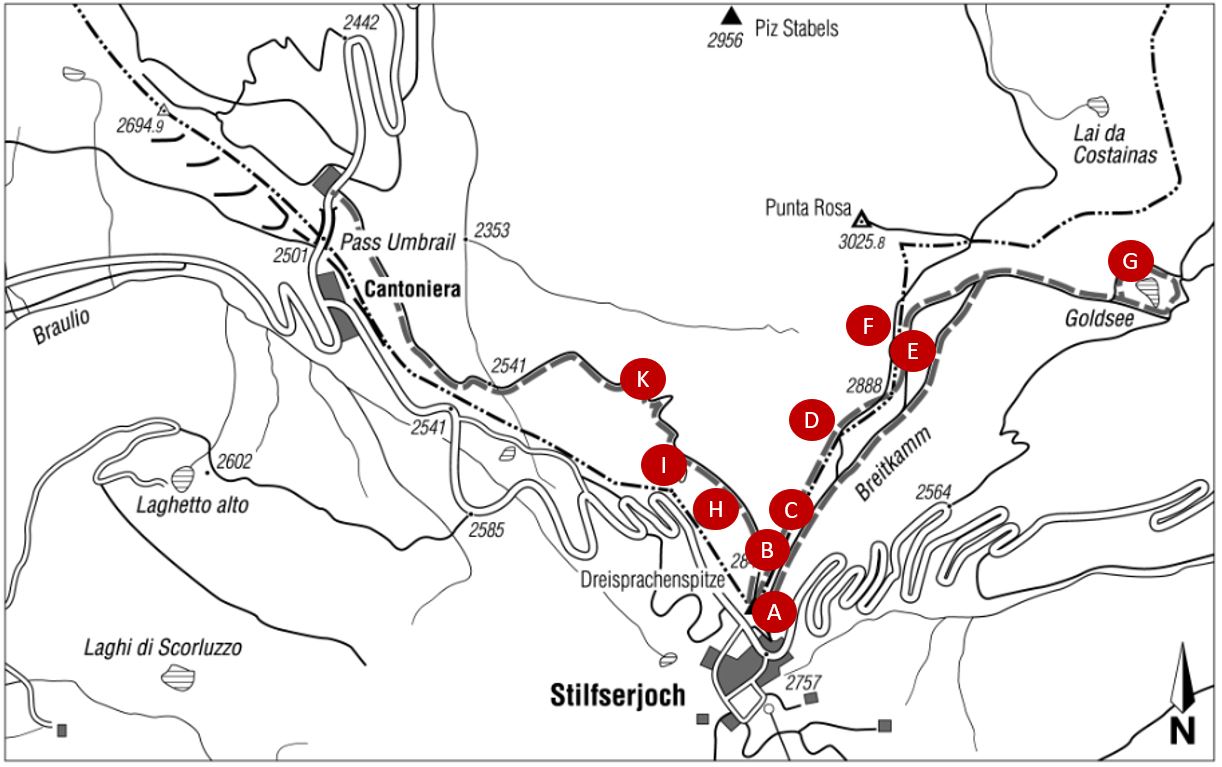

A: Ferdinandshöhe (Stilfserjoch) – B: Dreisprachenspitze – C: Hotel Dreisprachenspitze – D: Austro-Hungarian memorial plaque – E: Lempruchlager – F: ‘Hungerburg’ non-commissioned officer post – G: ‘Goldsee’ artillery emplacement – H: ‘Schweizergraben’ – I: ‘Frohburg’ non-commissioned officer post – K: mule track to Pass Umbrail

A DESCRIPTION OF THE ROUTE FROM A MILITARY-HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

A detailed description of the route can be found in the hiking guide ‘The Stelvio-Umbrail military-historical hiking trail’ from page 55 onwards. The following explanations highlight places along the trail and explain their historical significance.

The Stelvio Pass and its road construction

A road construction project in a class of its own! Built within six years from 1820-1826 under the direction of the k.k. Carlo Donegani, who was elevated to the Austrian nobility as Carl Donegani vom Stilfserberg in 1840. 48 hairpin bends on the north-east ramp (Prad in South Tyrol) and 34 hairpin bends interrupted by six tunnels lead from the Veltlin (Bormio) to the highest motorable Alpine pass. Today, the Stelvio Pass road attracts hundreds of thousands of cycling enthusiasts and motorbike fans every year, so that during the summer months there is hardly a free parking space to be found on the pass at 2757 metres above sea level. So much for the facts, but how did such a challenging road project come about in the first place?

Used again and again as a military road

Traffic over the Stelvio Pass was never of supra-regional importance. Goods were transported over the Umbrail Pass, which is 200 metres lower and objectively less dangerous. Nevertheless, regional trade between South Tyrol and Valtellina took place regularly. This crossing was used as early as the Bronze Age.

In Roman times, a mule track led over the pass, which was important from a military point of view. The crossing enabled the rapid movement of troops to protect the Via Claudia Augusta, which ran over the Reschen Pass.

The route followed the eastern (orographically left) side of the valley. From the settlement of Stilfs, the path led up to the Prader Alm and via today’s Furkelhütte (see ‘Kleinboden’) along the mountain flank to the Goldsee. It can be assumed that today’s hiking trail roughly corresponded to the route at that time, which was known as the ‘Wormisionssteig’ or ‘Wormser Steig’. Worms was the German name for Bormio and the Umbrail Pass was called ‘Wormser-Joch’ at the time.

However, the importance of the crossing should not be overemphasised. It was only used when troops needed to be moved, particularly during the Thirty Years‘ War. In 1633, for example, a Milanese army with 12,000 soldiers and 1,600 horses crossed the pass to support the Austrian Archduke Leopold. In 1634, the Spanish king’s brother led 21,000 soldiers into the Venosta Valley.

In the course of the Risorgimento – the unification of Italy with corresponding wars of liberation against the Habsburg Empire – military measures were once again called for. The then Austrian territories in Veneto and especially in Lombardy rebelled against Habsburg rule and the construction of an efficient military road was necessary to maintain peace and order. Troops needed to be moved from the Austrian heartlands to Milan as quickly as possible.

At the time of these uprisings (1815-1870), three Austrian emperors were entrusted with the leadership of the empire. Emperor Franz I (1804-1835), followed by his son Ferdinand I (1835-1848) and, after the ‘European revolutionary year of 1848’, his nephew, the legendary Franz Joseph I (1848-1916).

STELVIO PASS OR UMBRAIL PASS – A QUESTION OF NEUTRALITY

As already mentioned, goods were mainly transported via the Umbrail Pass. From the beginning of the 19th century, this route could be travelled by carts, but not by wagons. It was also used time and again to move troops from Lombardy to Tyrol and vice versa. An extension of this transit route would probably have been much less expensive than building a new road over the Stelvio Pass. Austria made corresponding offers, but these failed due to the decision of the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to impose neutrality on Switzerland. Although this allowed cross-border road construction, using the route to move foreign troops was beyond all politically interpretable possibilities.

DEVELOPMENT OF TOURISM

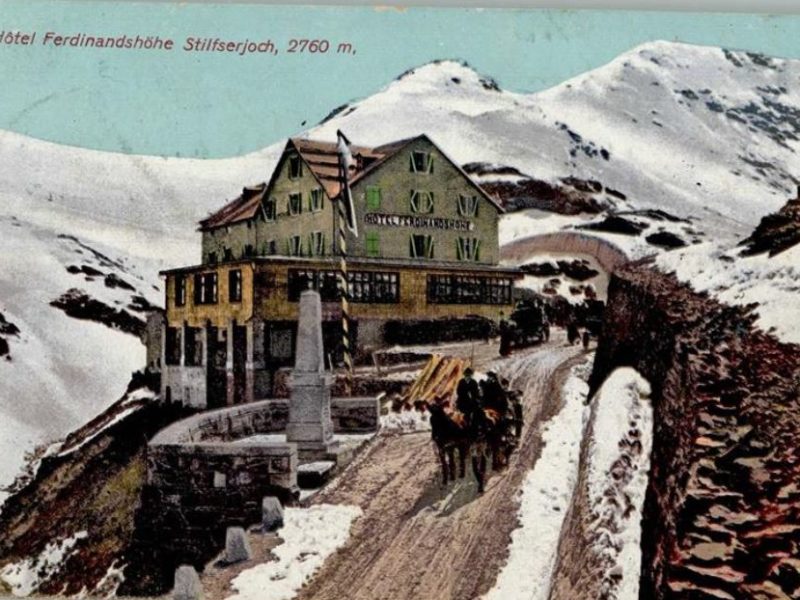

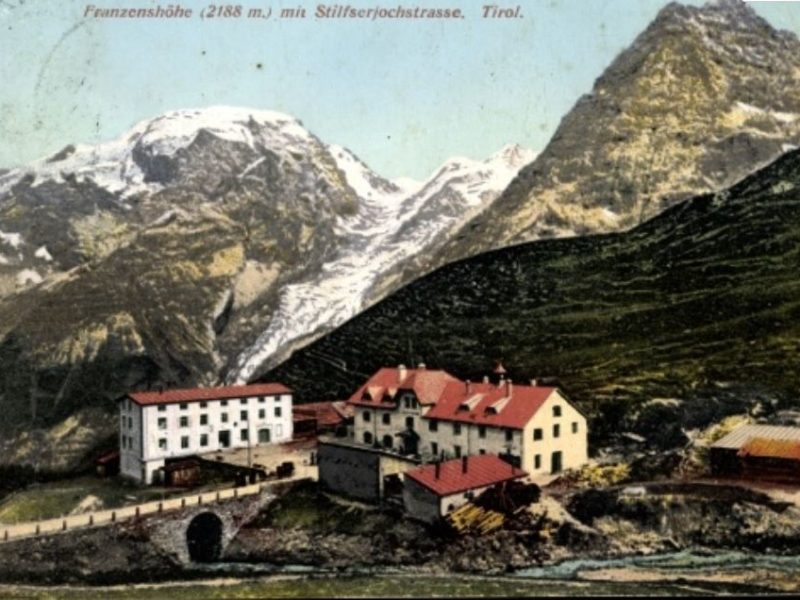

The construction of the road, but also the spirit of the times, meant that the Stilfserjoch also became a destination for wealthy people. Tourism in the Alps began to gain a foothold and regular postal services took travellers up and over the Alpine passes. As a result, appropriate accommodation was quickly built in the most scenic locations possible and appropriate catering was provided. Inns and even large hotels were built along the pass roads.

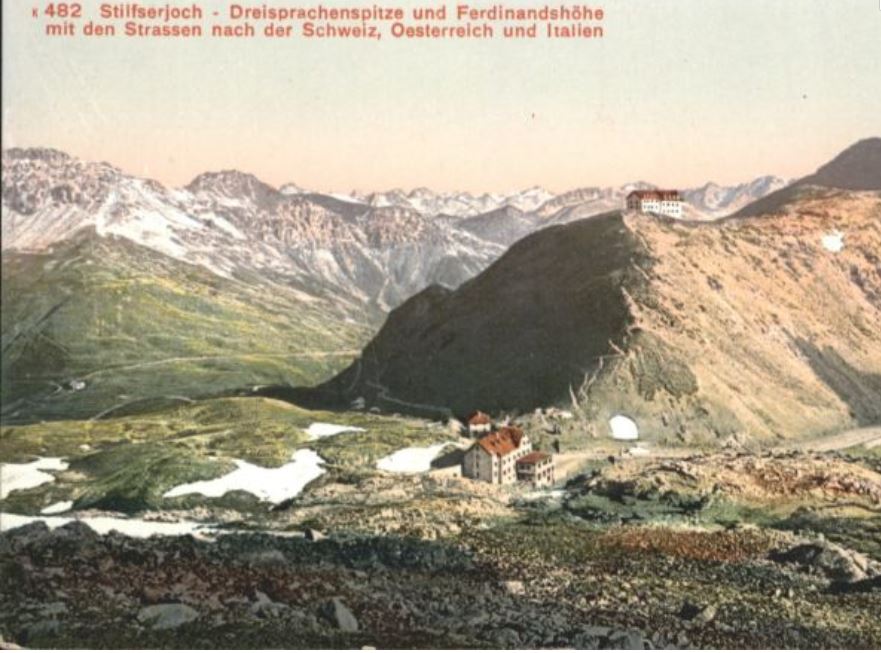

The Stelvio Pass with the hotels ‘Ferdinandshöhe’ and ‘Dreisprachenspitze’. On the left is the Italian road maintenance depot at the junction with the Umbrail Pass. Source: Postkartenlexikon.de

Ascent along the border

The short ascent from the Stelvio Pass to the Dreisprachenspitze follows a hairpin bend on the south-western slope and soon runs along the ridge that marked the border between Austria/Hungary and Italy until 1919. Today, this ridge marks the border between the two Italian provinces of Lombardy and South Tyrol.

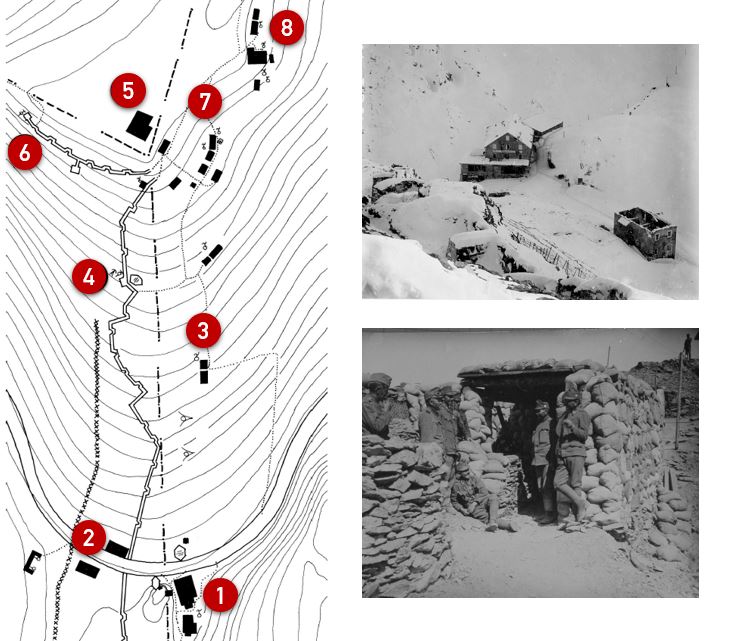

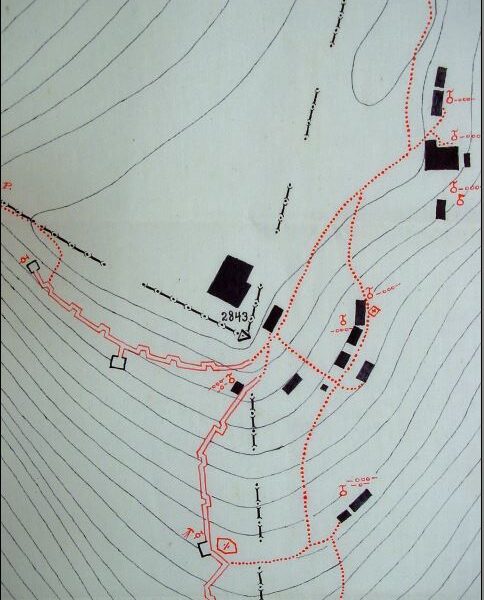

Once on the ridge, there is an impressive view of the Trafoi Valley with the 22 hairpin bends of the pass road between the Franzenshöhe and Ferdinandshöhe. Just a few metres east of the border line, we can see the foundations of what were once part of the Austrian defence line along this border ridge. The firing positions on the actual border were taken from these shelters on the rear slope. Today, only a few of these are still visible, as various tracks that have developed over the years make it difficult to identify them clearly. However, the following illustration makes it possible to locate them to some extent.

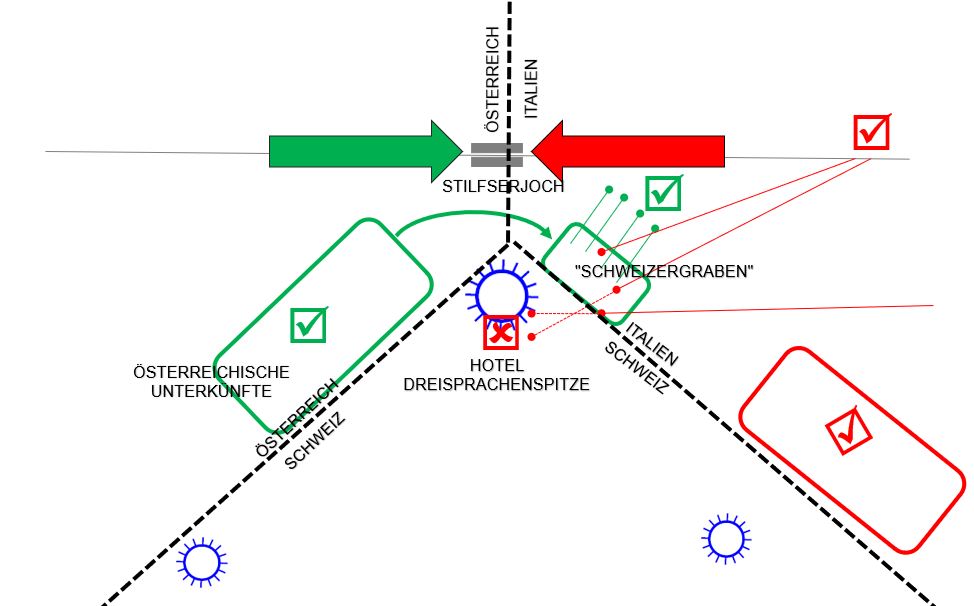

1. Ferdinandshöhe – 2. Haus Enzian (former Italian financial guard) – 3. Austrian accommodations on the rear slope – 4. Austrian machine gun post – 5. Hotel Dreisprachenspitze – 6. The Austrian ‘Schweizergraben’ – 7. + 8. Austrian accommodations protected by the Swiss border. Illustration: Accola based on the original site plan by Lempruch, archive: MUSEUM 14/18.

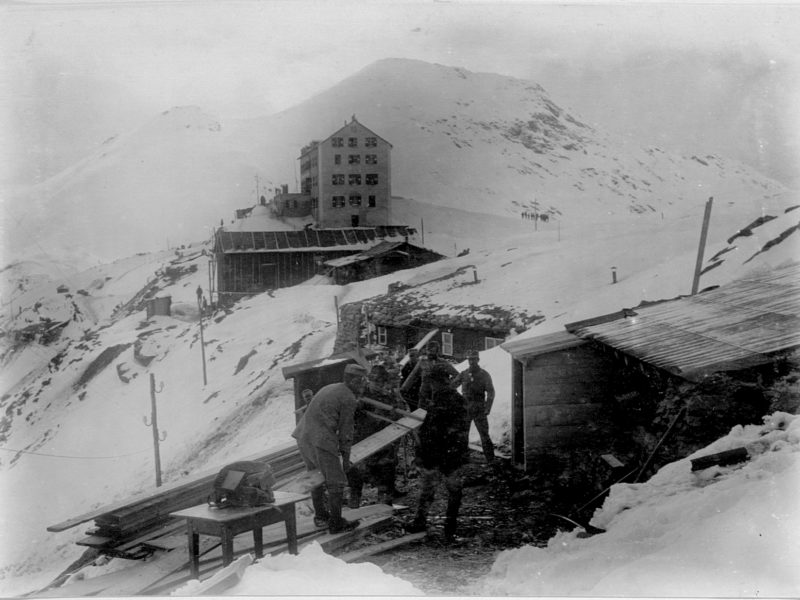

The two illustrations show the machine gun post (4) and the view from the Dreisprachenspitze towards the pass. Images: Imboden Collection, archive: MUSEUM 14/18.

The Mg position as it appears today. The materials used at the time are noteworthy. Concrete was in short supply on the Austrian side and was only used for very specific purposes. These included the foundations for cable cars, cooking stoves and exposed weapon positions. Otherwise, only stones from the immediate vicinity were used to build the wall.

The starting point on the Dreisprachenspitze

An insignificant point on the map at 2,843 metres above sea level with three different names. The Dreisprachenspitze – known as Piz da las trais Linguas in Romansh or Cima Garibaldi – was one of the key locations during the First World War. This is where the common border stone of Italy, Austria-Hungary and Switzerland once stood. This border stone – bearing the number 1 – is still there, at 2,850 metres above sea level. Since summer 2014, three iron figures have been guarding it and telling visitors about the remarkable history that took place here over 100 years ago.

The group of three mountain soldiers on the Dreisprachenspitze at sunrise in summer 2016. Left: the figure of an Italian Alpino with the typical feather on his hat; in the middle, an Austrian imperial rifleman with a hunter’s hat and plume; on the right, the Swiss infantryman with a shako and pompom. Installation: Verein Stelvio-Umbrail 2014; Image: Daniel M. Sägesser, Archive: MUSEUM 14/18.

The Dreisprachenspitze Hotel

The impressive building on the summit of the Dreisprachenspitze belonged to the Karner family from Prad. They also owned the Hotel Post, where the Austrian brigade command had set up its headquarters. The history of the Hotel Dreisprachenspitze is poorly documented, but various views (unfortunately not reliably dated) indicate that the building underwent several renovations and extensions.

Important to know: the current Ristorante Garibaldi was built in the 1950s and is not located on the same site as the wartime hotel. However, the foundation walls of the hotel are clearly visible and are located entirely on Swiss soil.

The Hotel Dreisprachenspitze seen from the Breitkamm, with Austrian lodgings on the left and the summit of the Kleiner Scorluzzo in the background behind the hotel. The Naglerspitze is visible on the left in the fog. Source: Imboden Collection, Archive: MUSEUM 14/18.

Use as military accommodation

After mobilisation in August 1914, Swiss troops confiscated the hotel as accommodation for their border guard detachments. The use of the building was contractually agreed with the Austrian owner family. With the outbreak of war (in 1914, Austria-Hungary was at war with Serbia and Russia), tourist travel collapsed and regular guests were no longer expected at the hotel. Accordingly, the Karner family is likely to have quickly agreed to the Swiss soldiers‘ intention to use the now empty building.

It should also be noted that Austria-Hungary’s defensive measures in the event of an expected outbreak of war with Italy were to first counter an Italian advance in the valley and surrender the actual Stilfserjoch pass without a fight. For them, the house was therefore of no military significance..

The border

The original boundary stones No. 1 and No. 2 still stand today, immediately south-east of the hotel, on what was once its terrace. While No. 1 marked the point where three countries met, No. 2 indicates the border with the Breitkamm, i.e. the border with the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Today, boundary stone no. 1, C.S stands for ‘Confederaziun svizra’, meaning ‘Swiss Confederation’ in Romansh. The year 1865 indicates the date of the survey or the year the boundary stone was erected. ‘R.I.’ on the south side stands for ‘Repubblica Italiana’. Behind it is the Ristorante Garibaldi, named after the Italian freedom fighter of the Risorgimento. Image: Marcia Phillips, Pro Monstein, 2009.

Boundary stone no. 2 and the marking of a supposed triangulation point for land surveying. It is unclear when this marking was added to the Dreisprachenspitze. This topographical point was of minor importance for surveying the national border. Visible behind the fog: the dominant peak of the Ortler. Image: Marcia Phillips, Pro Monstein, 2009.

The numbering of boundary stones is not consistent throughout Switzerland. There is also a boundary stone numbered 1 at the Basel-Weil border crossing, and there is one in Ticino and certainly others elsewhere. It is not clear how these numbers were assigned. Furthermore, not every stone was given its own number. Boundary markers between ‘independent numbers’ were then given an additional alphabetical designation, e.g. 1A or 12B. No. 1 was merely the starting point of a series of designations, which were then continued consecutively and – crucially – on both sides. Near the trilingual peak, there are therefore two boundary stones with the number 2 and two with the number 3, etc. Boundary stone No. 7 along the former Austrian border stands on the Rötlspitze, and the one along the Italian border near the Umbrail Pass is at the former non-commissioned officer’s post No. 7.

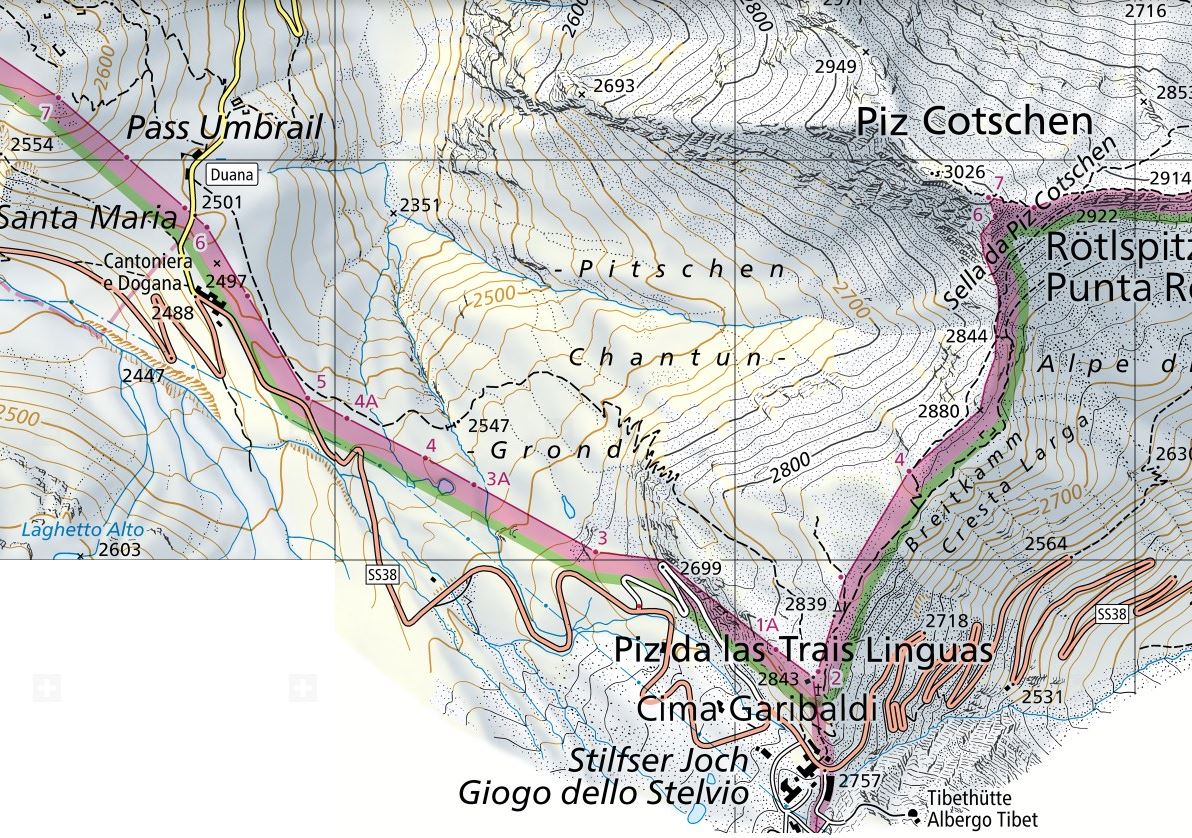

Boundary line and numbers of the corresponding markings in the affected area. Looking north-east, the (healthy) eye can see boundary stones No. 3 and, even better, No. 4 from stone No. 1. Knowledge of this line is important for understanding the border protection situation during the war years, as the border line on the Breitkamm is not as obvious as elsewhere. Map at: map.geo.admin.ch.

Peace and relaxation in the shelter of the neutral border

All foundation walls still visible to the right and east of this border line are of Austrian origin. The immediate proximity to neutral Switzerland offered Austrian troops the opportunity to ‘settle’ here safely and undisturbed, as this area was located directly behind the hillside, which prevented effective direct fire from the Italians. Artillery shells could only take effect far away from this area. This was particularly true of the Italian artillery positions on the Forcola and Monte Braulio. But the broad ridge also made the artillery on the Passo d’Ables a very difficult target to engage. If shells fired from the former position fell just a few metres short, they exploded on Swiss territory, which constituted a violation of neutrality. If they fell too short, they landed somewhere without causing any damage and also violated Switzerland’s neutrality, which was recognised by both sides. The same applied to fire from the Passo d’Ables: a few metres to the left meant shelling of neutral territory, a few metres too far to the right meant the shells landed somewhere on the steep slopes of the Breitkamm, but certainly had no effect in the immediate vicinity of the border.

It was therefore advisable for the Austrians to ‘settle down’ here in the immediate vicinity of the Dreisprachenspitze hotel and the border line and find peace and relaxation from the hardships and combat operations on the actual front.

The remains of a cooking stove on the Breitkamm bear witness to the long-term presence of Austrian troops under the protection of the Swiss border.

The Austrian troop camp on the Dreisprachenspitze and near the positions along the Italian border had a dual significance. On the one hand, it served as a retreat for soldiers who had to occupy the front line along the border ridge described above (see illustration above). On the other hand, the location also offered the opportunity to access the site safely by cable car and to ensure logistical services. Accordingly, the Breitkamm site not only contains the remains of accommodation huts and at least one kitchen, but also those of an ammunition depot, a medical aid station and the remains of the foundations of a cable car station.

Small border traffic

The immediate proximity to the Swiss border troops naturally led to frequent exchanges of ideas. There was also a lively exchange of food and war artefacts. Swiss chocolate was traded for Austrian ‘souvenirs’ such as dud bombs and tobacco pipes. The latter were even manufactured especially for the Swiss soldiers.

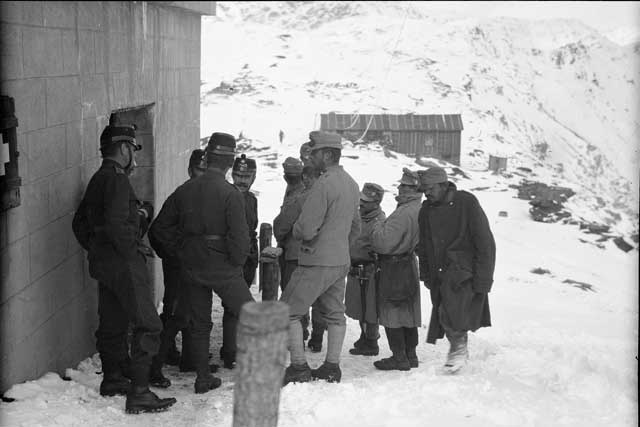

The boundary stones on the Dreisprachenspitze also became a meeting place for generals. Various photographs document such meetings.

Division Commander Schiessle and Colonel Bridler meet at the Dreisprachenspitze with Captain Andreas Steiner, the ‘hero of the occupation of Monte Scorluzzo’. On the right of the picture is the commander of the 76th Infantry Battalion, Major Joseph Müller. Image: Müller Collection, Archive: MUSEUM 14/18

Austrian officers meet with Swiss comrades at the geographical orientation board near the Hotel Dreisprachenspitze. The round marble board is now located on the terrace of the Ristorante Garibaldi. Image: Austrian State Archives Vienna, Digital: Archive MUSEUM 14/18.

LOGISTICAL CHALLENGE

Cable cars: the lifeline of supply

Supplying the mountain soldiers was a matter of utmost importance to everyone involved. ‘No food, no fight!’ This old soldier’s saying applied both at the front and across borders. In addition to food, wood was also on the daily list of requirements to fuel the sparse cooking and heating facilities in the high altitudes. Construction timber was also needed to erect new fortifications or maintain existing ones, and ammunition was always on the requisition list for their defence.

Providing all these goods in the valley was challenging enough. In the final years of the war, there was a shortage of everything. The daily supply of the front lines presented logisticians with additional, far more difficult tasks.

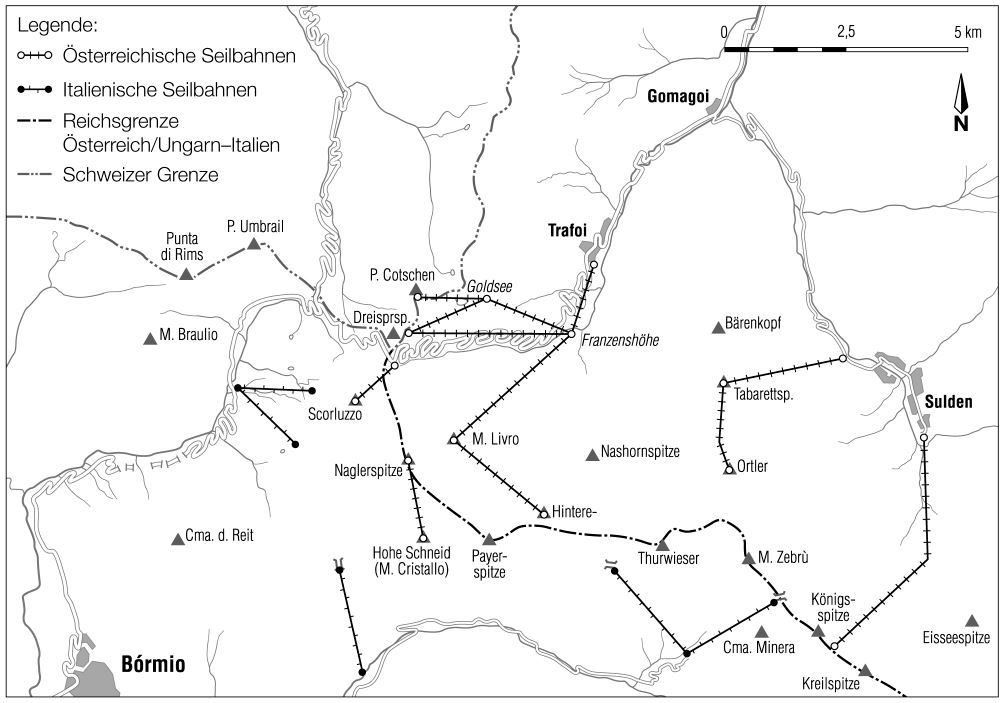

The availability of transport cableways was essential for supplying the high ground positions.

Both Italians and Austrians built large numbers of such railways along the entire front. Technical knowledge for constructing such facilities was virtually non-existent at the start of the war. Only Bavaria had so-called branch lines to supply remote farms, and so it was the German Alpine Corps that provided the Austrian army with the necessary expertise. It can be assumed that Italy, as a former ‘ally in the Triple Alliance’, also benefited from this knowledge.

Switzerland completely refrained from using transport cableways. Military cableway construction in the Swiss Confederation did not begin until after the First World War.

Overview of transport cableways built in the Ortler region until the end of the war. Illustration from: Accola/Fuhrer, Stilfserjoch-Umbrail 1914-1918, Documentation, Military History You Can Touch, Au, 2000.

SUPPLYING THE FRONT

Franzenshöhe was the hub of supply along the Ortler front. Before the four branch lines could transport goods from this location to the positions, the necessary materials had to be brought there. It is therefore worth taking a look at the preceding links in a delicate transport chain.

Goods from the Reich territory were transported by rail via the Brenner line (opened in 1867) or the Puster Valley (opened in 1871) to Bolzano and on to Merano, which had been connected to the Brenner line via a standard-gauge connection since 1881. In Merano, the goods were transferred to narrow-gauge railway vehicles through the Vinschgau Valley, which was opened in 1906.

After another 50 kilometres, the Vinschgerbahn reached the small station of Spondinig, an inconspicuous hamlet on the eastern edge of the municipality of Schluderns. Here, the railway wagons were unloaded and the goods temporarily stored.

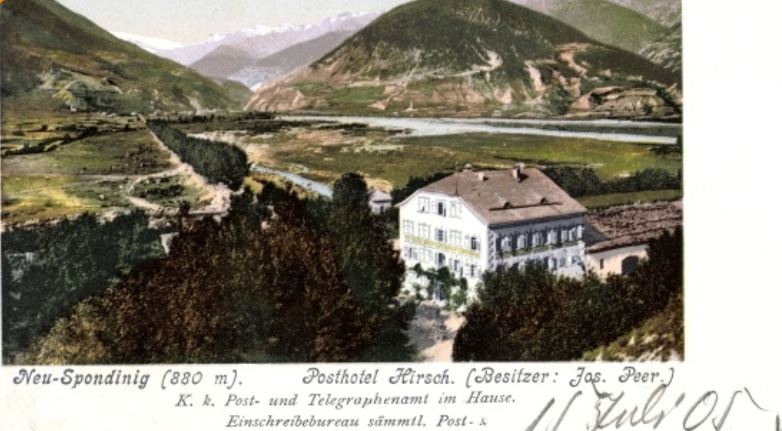

Spondinig, a few kilometres northeast of Prad, at the junction of the Stilfserjoch road, on a postcard from 1905. The Posthotel Hirsch opened in that year and housed the stage command and, in particular, the military hospital during the war years. The Stilfserjoch pass can be seen at the lowest point on the horizon. Image: Postkartenlexikon.de

THE STAGE

Spondinig was operated in a broader sense as a staging area, a logistical supply facility. This is where the rear services such as military hospitals, supply trains, administrative and maintenance units were located. The members of the supply train were then responsible for transporting the goods to the supply points near the front. Trucks were used for this purpose, but carts were also used in particular. Finally, pack horses and even dogs were used for transport.

MEDICAL SERVICES

The care and specific treatment of sick and wounded soldiers was also the responsibility of the rear echelon. However, the rescue and transport of the affected persons to appropriate facilities was the task of the frontline troops. For this purpose, the units had a medical patrol with four ‘wound bearers’.

The command assumed that approximately 10% of each unit would be wounded during and after combat. Of these, 25% were expected to be killed, 25% seriously wounded and 50% suffer injuries resulting in minor wounds. With an average unit strength of 140 men, 14 soldiers were expected to be seriously injured and rescued via the so-called ‘patient route’.

Initial treatment was provided at the scene by comrades. For this purpose, each soldier had a ‘first aid kit’ containing items for disinfecting and dressing gunshot and shrapnel wounds.

They were then transported by stretcher bearers to the first facility supervised by a doctor, known as the ‘aid station’. One such station was also operated at the Dreisprachenspitze, where initial triage was carried out to separate the seriously wounded from the lightly wounded. The latter were transferred to a ‘lightly wounded station’. Depending on their recovery, the patients were either returned directly to the troops or, after a stay in the ‘field hospital’, a decision was made on their further use.

The seriously wounded were admitted to the ‘dressing station’, where measures comparable to those taken in today’s emergency rooms and intensive care units in hospitals were taken. Surgical procedures, including amputations, were on the list of tasks for a large number of doctors and nurses. The locations of these dressing stations in Defence District I cannot be conclusively proven. It is possible that one was set up in Prad.

If the patient survived the operation, they were taken to a ‘field hospital’ which was operated for the Ortler section in Spondinig. It is conceivable that the ‘dressing station’ was also located here. Sad evidence for this assumption is provided by the immediate vicinity of the ‘war cemetery’, which was always built near dressing stations or field hospitals.

Literature: There are numerous publications on medical services in the First World War. Recommended reading: Lüchinger Stephan / Brunner Theodor ‘Verwundetentransport im Ersten Weltkrieg’ (Transport of the wounded in the First World War), GMS annual publication 2004.

The ‘Lempruch camp’

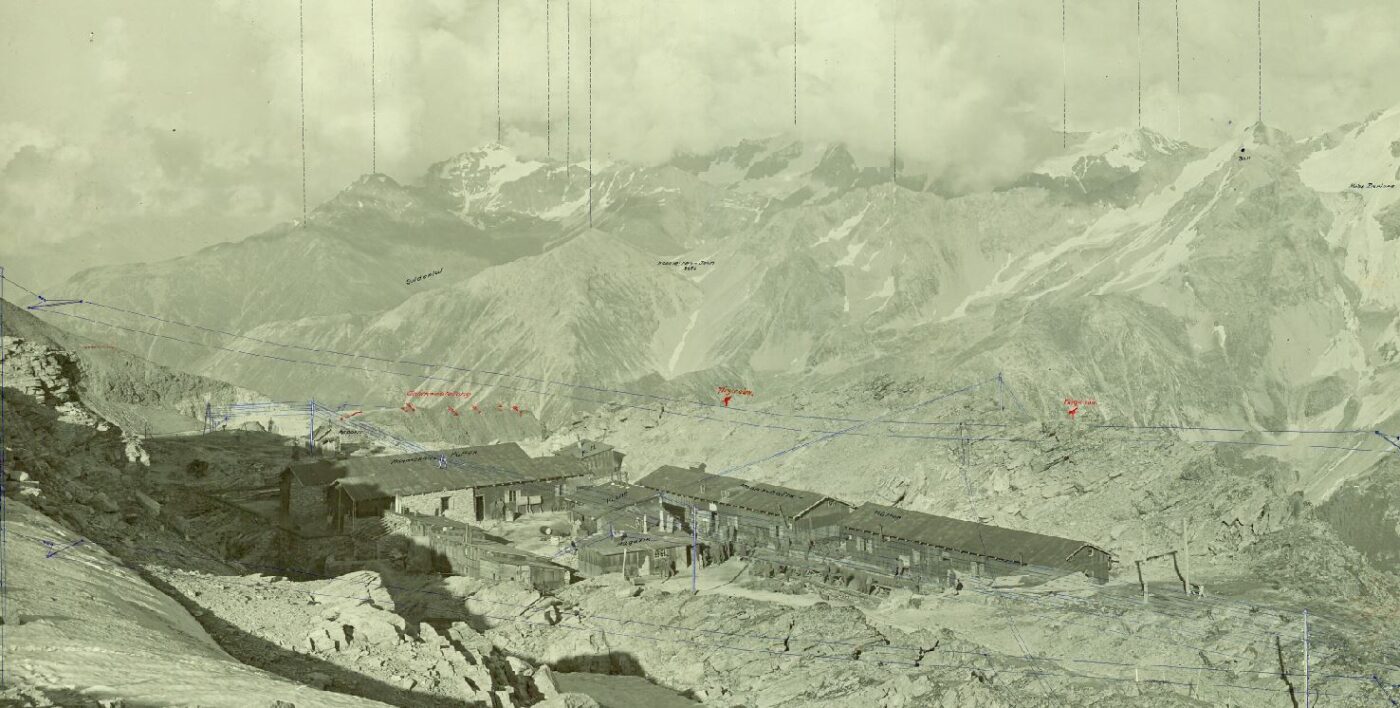

About one kilometre northeast of the summit of the Dreisprachenspitze, we come across the remaining foundation walls of an impressive accommodation complex. The outlines of barracks, kitchen facilities and the concrete anchoring of a cable car station can be seen, which was used to supply this location from the Franzenshöhe. These facilities were named after the second commander of Defence District I, Colonel Moritz Erwin Freiherr von Lempruch, and were recorded as the ‘Lempruchlager’ in field files and later historiography.

The ‘Lempruch camp’ in the immediate vicinity of the Swiss border, photographed by the Swiss Army’s news section in 1917. Source: Federal Archives, inventory E 27, archive: MUSEUM 14/18.

In Lempruch’s camp – which included the other facilities along the ridge – there was almost everything a soldier, and especially an officer, could wish for. There was a bathhouse, sources also mention a ‘casino with the possibility of projecting moving images’, in front of the accommodation huts there were ‘herb gardens’, physical and health needs were taken care of, and the first anti-aircraft guns ensured protection against attacks from the air. The local power supply provided electric light, and telephone lines enabled communication with the front lines and facilities in the valley.

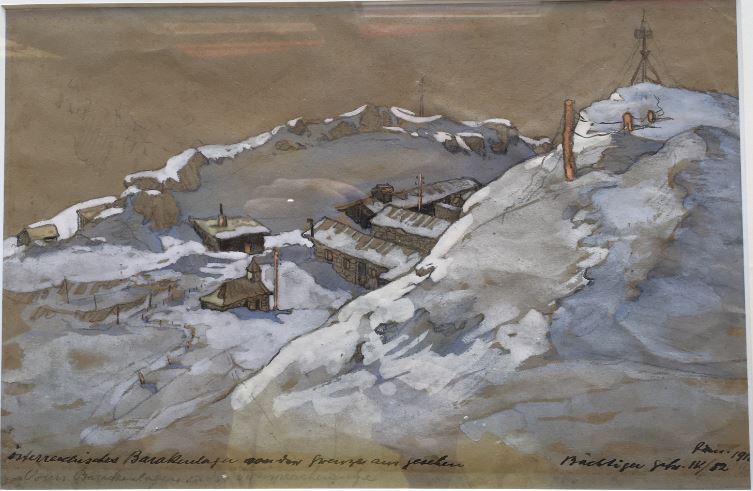

Troops returning from the front lines were to be able to recover here, and the ‘Lempruch camp’ offered almost all the amenities they could expect. These included a chapel, the floor plan of which we can no longer find today, but whose existence is documented in photographs and artistic illustrations.

The Lempruch camp in a painting by Swiss church painter Augustin Meinrad Bächtiger (born 12 May 1888 in Mörschwil, died 4 May 1971 in Gossau), who served as a border guard in the St. Gallen Fusiliers Battalion 82, which was stationed on the Umbrail Pass and the Dreisprachenspitze in January 1917. The chapel of the Lempruch camp can be seen on the left of the picture. On the right is the location of the Swiss non-commissioned officers‘ post. Image: From the family’s collection, digital copy in the archive: MUSEUM 14/18.

MORITZ ERWIN FREIHERR VON LEMPRUCH

Anyone interested in the events of the war along the Ortler front will repeatedly encounter the name ‘Lempruch’. Chapels, bridges and streets bear his name and commemorate the charismatic commander of Defence District I. Honorary citizenship awards from Glurns, Prad, Stilfs and Taufers testify to his close ties with the local population.

Lempruch was born on 23 April 1871 in the Duchy of Carniola, now Novo Mesto in Slovenia. His father (Anton) was a colonel in the Imperial and Royal Army, and little is known about his mother (Alice) except for her dates of birth and death. Moritz was the couple’s third son and grew up well protected in his father’s various garrison towns.

After graduating from high school in 1887, he intended to study at a technical university, but his father believed that Moritz Erwin ‘had to serve the emperor and the empire as an officer.’

Colonel Moritz Erwin Freiherr von Lempruch, ‘Portrait of the Author,’ as he himself described the image in his work ‘Ortlerkämpfe – Der König der Deutschen Alpen und seine Helden’ (Battles on the Ortler – The King of the German Alps and His Heroes).

Colonel von Lempruch (centre), flanked by his front commanders Kalal, Hyza, Molterer and Cassek (from left to right); image from: Lempruch, the King of the German Alps and his heroes, collection: Knoll, archive: MUSEUM 14/18.

Accordingly, he attended the three classes of the engineering department at the Imperial Military Technical Academy at Stiftgasse 2 in Vienna as a ‘pupil’ until 1890, graduating with average results.

His certificate attests to his ‘fairly quick comprehension, cheerful, respectful and characterful disposition, and courteous, very decent behaviour.’

At the age of 19, the newly qualified lieutenant of the Railway and Telegraph Regiment began his professional career in the Imperial and Royal Army. In addition to his duties in the regiment, he attended several further training courses, mainly in the field of engineering. In 1899, a report from the military academy records his training in the following subjects: tactics, strategy, fortifications, artillery, military geography, construction engineering, electrical engineering and French.

He was then assigned to the staff of the Engineering Directorate in Trento, where he was deployed to construct various defensive positions in the Fiemme Valley (Val di Fiemme) and at the Passo di Rolle.

In 1900, Lempruch was appointed captain and in 1908 recommended for promotion to major in the engineering staff. Two years later, he received the corresponding promotion. In addition to Vienna, sources mention Korneuburg, Trento, Theresienstadt, Krakow and other locations as places of service.

From 1910 to 1913, he taught engineering subjects at the Military Academy.

At the beginning of the war, he was involved in barrier installations in Tyrol and served as a lieutenant colonel in the Engineering Directorate in Brixen. From December to March 1915, he assisted in the construction of fortifications in Galicia, where he was deemed to have been ‘in enemy fire’.

After Italy declared war, he returned to Brixen, where he temporarily fell ill with dysentery and was promoted to colonel on 1 September 1915. In this capacity, he commanded the combat group on the Folgaria plateau from October 1915 and, in March 1916, following the sudden death of Colonel Abendorf, was appointed his successor as commander of the defence sector on the Ortler.

Lempruch had been married to Maria-Viktoria Countess Sizzo-Noris since 1905. Two children, a daughter Maria-Alix (1906) and a son Karl Heinrich (1907), were born from this union. Another son (1917) was born from an extramarital relationship with his housekeeper in Prad.

After the war, the von Lempruch family settled in Innsbruck, where the retired colonel wrote down his memories of the front, which were published in 1925 in the richly illustrated work ‘Der König der Deutschen Alpen und seine Helden – Ortlerkämpfe 1915/1918’ (The King of the German Alps and his Heroes – Battles on the Ortler 1915/1918). In the meantime, he was promoted to Major General in the reserve, probably in recognition of his achievements and to increase his pension contributions. No other reasons can be substantiated.

The pensioner, who had been widowed since 1930, spent his twilight years in Wiedendorf (now Strass im Waldviertel) in Lower Austria. He died on 19 February 1946 at the age of 75 and was buried in Elsarn.

Literature: In his account of the events of the World War, Lempruch provides little information about himself. His work has been republished in an expanded form. Recommendation: Heinz König: ‘Gedenke, O Wanderer…’ (Remember, O Wanderer…): biographical mosaic about Moritz Erwin Freiherr von Lempruch, retired Major General. Autonomous Region of Trentino-South Tyrol, no place, 2012 and Helmut Golowitsch (ed.): Ortlerkämpfe 1915–1918. Der König der Deutschen Alpen und seine Helden von Generalmajor Freiherrn von Lempruch (The Ortler Battles 1915–1918. The King of the German Alps and his heroes by Major General Freiherr von Lempruch), supplemented by historical contributions, Buchdienst Südtirol, Nuremberg, 2005.

The ‘Goldsee’

Two kilometres to the northeast, almost at the same height as the Dreisprachenspitze, are the remains of the former artillery position ‘Goldsee’.

Artillery observer shelter in the Goldsee position. Image: Archive MUSEUM 14/18

The choice of this location for artillery guns and the materials used for the expansion raise questions. The remaining building ruins indicate solid construction. In contrast to the facilities along the ridge, concrete was used and the entire complex does not give the impression of a temporary installation. If we consider the original defence concept of the Austro-Hungarian Army to repel an Italian attack via the Stelvio Pass, much becomes clear. What can be found here was built around 1912 and formed the left flank protection of the Gomagoi fortress. Further information can be found on the page ‘Kleinboden’.

The guns stationed here were mainly effective in the first days of the war. Cannons and howitzers successfully supported the daring operation to occupy Monte Scorluzzo in the days leading up to it.

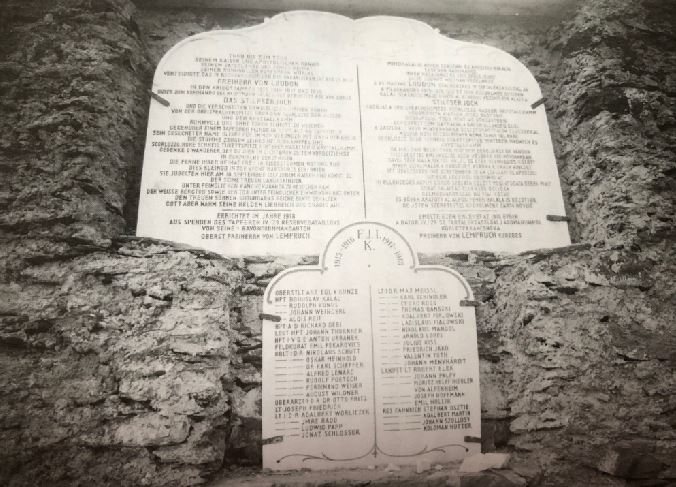

A monument with a special history

A few metres from the Dreisprachenspitze, just before boundary stone no. 3, we find three special commemorative plaques on Swiss soil. The inscription on the marble slabs commemorates the ‘heroic struggle’ of Austro-Hungarian soldiers along the Ortler front with the following words:

TREU BIS ZUM TODE

SEINEM KAISER UND APOSTOLISCHEN KÖNIG

SEINEM VATERLANDE UNS SEINER HEIMAT,

SEINER RUHMVOLLEN VORFAHREN WÜRDIG,

VERTEIDIGTE DAS IV. RESERVEBATAILLON DES UNGARISCHEN INF. REGTS. NR. 29

FREIHERR VON LOUDON

IN DEN KRIEGSJAHREN 1915, 1916, 1917 UND 1918

UNTER DEM KOMMANDO DES HAUPTMANN KALAL U. DES OBERSLTS. EDL VON KUNZE

DAS STILFSERJOCH

UND DIE VERSCHNEITEN, UNWIRTLICHEN, EISIGEN HÖHEN

VON DER DREISPRACHENSPITZE ÜBER DEN SCORLUZZO, DEN NAGLER

UND DEN KRYSTALLKAMM

RUHMVOLL UND OHNE EINEN SCHRITT ZU WEICHEN

GEGENÜBER EINEM TAPFEREN FEINDE IN MEHR ALS 40 GEFECHTEN.

SEIN GESEGNETER NAME BLEIBT FÜR IMMER VERBUNDEN MIT JENEN DER BERGE,

DIE STUMME ZEUGEN SEINES HELDENKAMPFES SIND:

SCORLUZZO, HOHE SCHNEID, TUKETTSPITZE, HINTERER MADATSCH U. KRYSTALLKAMM.

GEDENKE O WANDERER, DER DU HIER IN LICHTEREN ZEITEN VORBEIZIEHST

IN EHRFURCHT DERJENIGEN,

DIE, FERNE IHRER HEIMAT, TREU IN EISESSTÜRMEN, NOT UND TOD

DIES KLEINOD IN DER KRONE HABSBURGS SCHIRMTEN;

SIE JUBELTEN HIER AM 16. SEPTEMBER 1917 IHREM KAISER UND KÖNIG ZU,

DER SEINE TREUEN LANDESKINDER

UNTER FEINDLICHEN KANONENDONNER ZU BESUCHEN KAM.

DER WEISSE BERGTOD SOWIE DER TOD UNTER FEINDLICHER EINWIRKUNG HAT UNTER

DEN TREUEN SÖHNEN SÜDUNGARNS REICHE ERNTE GEHALTEN;

GOTT ABER NAHM SEINE HELDEN LIEBREICH UND GNÄDIG AUF.

ERRICHTET IM JAHR 1918

AUS SPENDEN DES TAPFEREN IV./29. RESERVEBATAILLONS

VON SEINEM RAYONSKOMMANDANTEN

OBERST FREIHERR VON LEMPRUCH

With the exception of the language, which seems somewhat archaic to us today, there appears to be nothing unusual here – but why is this monument located in Switzerland?

The marble plaques from Laas on the Breitkamm. On the left is a diptych with the names of 44 officers, in the centre is the text reproduced above in German, and to the right is the Hungarian version. At the top of the two plaques, you can see the Habsburg crown (left) and the Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen. Photo taken in 2016, after completion of extensive restoration work by the Stelvio-Umbrail 14/18 Association.

The memorial plaques are no longer in their original location. Their arrangement also differs from the original layout. The exact date of their erection is unknown, but the inscription mentions the last year of the war (1918) as the year of construction. However, the diaries contain no references to the reason for the memorial or the form of its inauguration. It can be assumed, however, that this took place in a dignified manner as part of a field mass.

The story behind the story

In the course of the far-reaching measures to Italianise South Tyrol, the monument fell victim to an act of vandalism. Whether this was an officially ordered action or a spontaneous act by fascist supporters cannot be determined. After South Tyrol was ceded to Italy (1919), the government eliminated everything recognisable that reminded people of the time of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Double-headed eagles were removed from official buildings, inscriptions were painted over… but this is a story after the story and would inevitably go beyond the scope of further explanations.

We know that in July 1953, a group of history students from the University of Zurich on a study trip led by the legendary Prof. Marcel Beck were informed by a Swiss border guard about the whereabouts of the marble fragments. These were found not far from their former location on the slope leading to the Stilfserjoch road and were recovered by the group in a ‘cloak-and-dagger operation’. Swiss border guards from the Umbrail post were then tasked with assembling the fragments into a temporary monument. The location of this memorial, which stood for the next 20 years, is unknown and, unfortunately, there is no photographic evidence of it.

Marcel Beck visited the Dreisprachenspitze once again in 1972 and decided to take measures that would contribute to the ‘complete rescue of the monument’.

The restoration of the marble slabs, consisting of 14 fragments and some missing parts of the inscription, was carried out in the marble workshop in Laas, where the originals had been made in 1918. The original head section of the diptych with the inscription 1915-1916 F.J.I. (for Emperor Franz Josef I) and 1917-1919 K. (for Emperor Karl) remained missing and was not reconstructed. The project was once again financed by donations, this time mainly from the members of the Officers‘ Association of the Canton of Graubünden and the Lions Club Val Müstair.

In 1976, the panels were to be erected on the Breitkamm at their current location. Emperor Karl’s son, Otto von Habsburg (1912–2011), and his mother, Empress Zita (1898–1989), who was living in Zizers at the time, were not present at the inauguration of the memorial, but letters of thanks for their moral support demonstrate the gratitude of the House of Habsburg for this initiative.

A dreamlike place to reflect on the past and the future. In the background, the Piz Umbrail is under construction. Image: Archive MUSEUM 14/18.

The ‘Schweizergraben’

Don’t leave the Dreisprachenspitze without taking a look at another special feature. At the foot of the terrace of today’s Ristorante Garibaldi, a few metres to the north-east, you can see the course of a trench that was of special significance. There are various names for it. Sources refer to it as the ‘Schweizergraben’ (Swiss trench), the ‘Lebensversicherung’ (life insurance) and also the ‘Paradegraben’ (parade trench) as common place names.

This Austrian defensive position ran along the border with Switzerland, which was already Italian territory at the time. Exactly means here: two metres from the border.

This trench caused the Italians some concern, as it was almost impossible to fight the enemy from this position. Any shots fired inevitably resulted in projectiles or ricochets landing on Swiss soil, which was tantamount to a violation of the neutrality of the Swiss Confederation, recognised by both sides.

Schematic representation of the border situation at the trilingual peak, assessed in accordance with neutrality law requirements. In blue: Swiss bases, in green: Austrian facilities and movements, in red: Italian positions and measures. Actions permitted under neutrality law are indicated by a correction mark, border violations by an ‘X’. Illustration: Accola, in ‘100 Years of the First World War’, lecture series 2014, archive MUSEUM 14/18.

The Italians therefore intervened against the use of this Austrian facility as a trench against the commander of the Swiss troops. If the enemy continued to fire from the ‘Swiss trench’, Italy would respond with artillery fire, even if this meant violating the border.

The Swiss officers responded pragmatically: ‘Then we will withdraw from the trilingual peak and only guard the border at the Umbrail Pass.’ This could not be in Austria’s interest, as neutral Switzerland guaranteed the protection of its accommodation facilities on the Breitkamm.

Through Swiss mediation, a unique compromise was reached: observation from the ‘Schweizergraben’ was permitted, but firing from it was not. The original combat trench was now an observation post and soon became a ‘parade trench’. The agreements reached suggested that this position was unlikely to come under fire. Anyone who entered the trench was therefore ‘on the safe side,’ and so the generals mainly used this location during their visits to the front to inspect the troops ‘under cannon fire.’ The alternative name for the trench, ‘life insurance,’ is therefore understandable.

Emperor Karl (1887-1922) visiting on 16 September 1917. The picture shows the monarch after returning from his visit to the ‘Paradegraben’, which was connected to the trench system in the positions on the border ridge (see also illustration ‘Ascent along the border’). Image: Knoll Collection, MUSEUM 14/18 Archive.

The ‘military track’

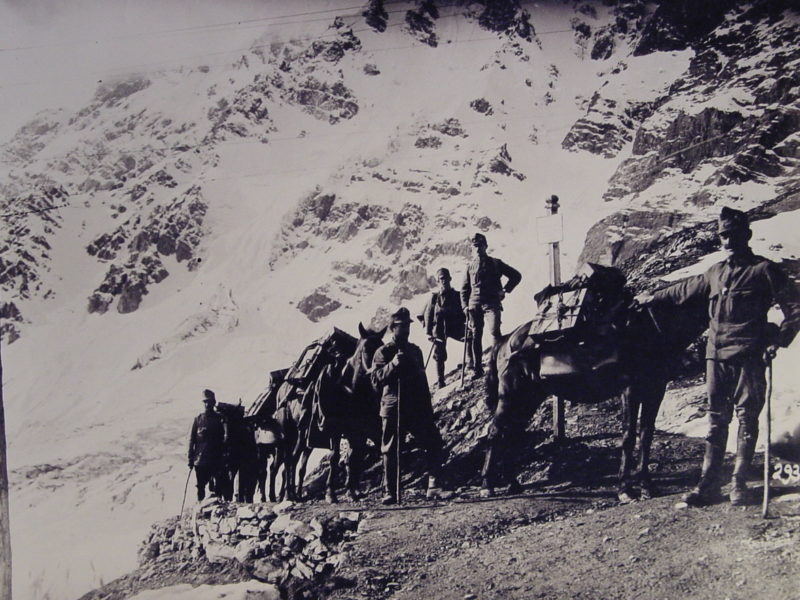

Although the name is not particularly appealing, this is what the Swiss supply route to the Dreisprachenspitze peak from the Umbrail Pass is known as locally. Ideally, convoys of pack animals would set off from the middle of the Umbrail Pass to supply the officers‘ post on the Dreisprachenspitze peak with goods, but transport often involved a great deal of effort and was carried out on foot.

Sixteen hairpin bends overcome an altitude difference of almost 400 metres along a path that was built by the 6/3 Sapper Company in the second year of the war. Along the way, we come across two Swiss non-commissioned officers‘ posts – the “Frohburg” near boundary stone no. 3 and the “Splitterheim” near stone 6A.

The ‘military track’ from the Umbrail Pass to the Dreisprachenspitze peak, photographed by the Archaeological Service of the Canton of Graubünden in 2013. As part of an inventory of archaeological monuments, this route was recorded and classified as historically significant, and a conservation project was launched. Image: Archive MUSEUM 14/18.

The retaining walls and rain deflectors of the ‘military track’ are currently in a deplorable state. Even though a project to renovate the hiking trail is underway, care is still needed. We would particularly ask the many mountain bikers who often use this trail, unaware of its historical significance, to be considerate.

The ‘Lempruch camp’ as it stands today. Image: Archive MUSEUM 14/18.

Would you like to explore the hiking trails accompanied by experts?

You are in the right place on this page.